All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Distinctive prognostic factors in patients with thrombocytopenic myelofibrosis

Thrombocytopenia is an adverse prognostic factor for myelofibrosis (MF) and presents several treatment-related challenges, including dose changes and treatment cessation, as well as exclusion from clinical trials.1 MF with thrombocytopenia has been considered a high-risk disease and associated with poor survival.1

Kuykendall, et al.1 conducted a study with the aim of investigating whether all patients with thrombocytopenia present with the same high-risk features or if any distinct characteristics within these patients would inform a different approach for risk stratification. The results were recently published in Cancer, and we summarize their findings below.

Study design

This retrospective cohort analysis identified patients from a database between 2001 and 2021. Clinical variables were recorded at diagnosis, while patients who had no available clinical data prior to receiving MF-associated therapy were excluded.

Patients with a pretreatment platelet count <100 × 109/L were compared with those with a preserved platelet count of >150 × 109/L. Patients with a platelet count between 100 × 109/L and 150 × 109/L were excluded.

Results

A total of 137 patients with baseline thrombocytopenia (<100 × 109/L) were selected and compared with 628 nonthrombocytopenic patients (>150 × 109/L). The median follow-up time was 53.9 months. Full patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics*

|

Hgb, hemoglobin; MF, myelofibrosis. |

|||

|

Variable, % |

Thrombocytopenic (platelet count <100 × 109/L) n = 137 |

Nonthrombocytopenic (platelet count >150 × 109/L) n = 628 |

p value† |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Median age at diagnosis, years |

68 |

67 |

0.33 |

|

Primary MF |

77 |

63 |

0.03 |

|

Post-polycythemia vera MF |

16 |

14 |

0.06 |

|

Post-essential thrombocythemia MF |

7 |

22 |

<0.01 |

|

Hgb <10 g/dL |

55 |

33 |

<0.01 |

|

Peripheral blasts ≥1% |

34 |

21 |

<0.01 |

|

Marked marrow fibrosis |

61 |

51 |

0.03 |

|

Bone marrow cellularity ≤20% |

19 |

5 |

<0.01 |

|

Albumin <4.3 g/dL |

67 |

44 |

<0.01 |

|

High- or very high-risk cytogenetics |

41 |

30 |

0.02 |

|

Deletion 20q |

19 |

10 |

<0.01 |

|

JAK2 mutation |

72 |

69 |

0.68 |

|

JAK2 mutation allele burden ≥60% |

26 |

42 |

0.03 |

|

CALR mutation |

7 |

19 |

<0.01 |

|

MPL mutation |

7 |

7 |

0.7 |

|

U2AF1Q157 mutation |

25 |

6 |

<0.01 |

|

≥3 nondriver mutations |

43 |

26 |

<0.01 |

Patients with thrombocytopenia were more likely to have primary MF (p = 0.03) but were less likely to have MF after a diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia (p < 0.01). Patients with thrombocytopenia were also more likely to have a range of other symptoms and features, including anemia, peripheral blasts >1% and either high or very high-risk cytogenetics. There was no difference in the incidence of splenomegaly, leukocytosis, constitutional symptoms, and frequency of JAK2 mutations.

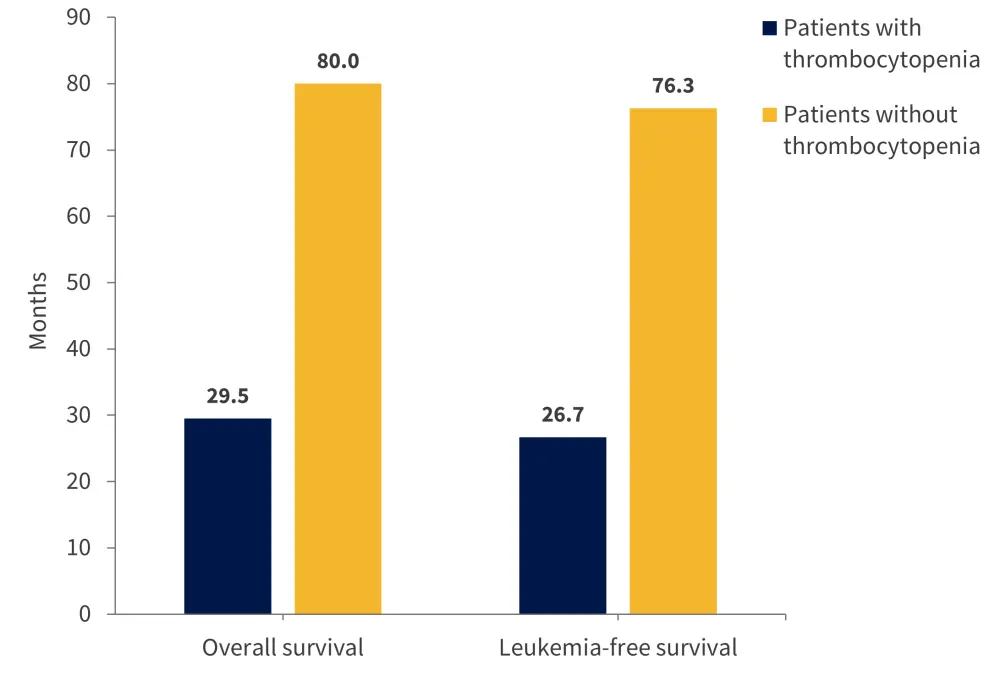

Interestingly, patients with thrombocytopenia were less likely to have a CALR mutation (p < 0.01). Among those with thrombocytopenia, 61% had one or more genetic abnormality. While anemia was more frequent in these patients, those with del(20q) were less likely to have concomitant anemia (33% vs 59%; p = 0.02). High/very high-risk cytogenetics had a greater chance of association with significant marrow fibrosis (p = 0.02). Overall survival (OS) and leukemia-free survival showed no difference based on genetic abnormalities. There were also similar rates of transformation to blast phase in patients with or without thrombocytopenia (12% vs 9%, respectively; p = 0.43). However, overall, patients with thrombocytopenia had a significantly shorter median OS and leukemia-free survival compared with patients without thrombocytopenia (p <0.01 for both variables; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Median overall survival and leukemia-free survival in patients with and without thrombocytopenia*

*Adapted from Kuykendall, et al.1

Moreover, patients with thrombocytopenia were less likely to receive JAK inhibitor therapy compared with those without thrombocytopenia (35% vs 53%, respectively; p < 0.01).

Univariate analysis of patients with thrombocytopenia revealed several variables associated with inferior OS, including:

- Age >65 years at diagnosis (p = 0.01)

- Marked fibrosis (p = 0.05)

- Albumin levels <4.3 g/dL (p = 0.02)

- EZHZ mutation (p = 0.04)

- TP53 mutation (p < 0.01)

Subsequent multivariate analysis initially included all clinical variables that were at least borderline significant (p < 0.1) in the univariate analysis, which revealed only serum albumin levels <4.3 g/dL to be a significant covariate (p = 0.2). A second multivariate analysis, performed in a genetically annotated subgroup, included all genetic variables. This demonstrated that the presence of SRSF2 or TP53 mutations significantly impacted OS (p = 0.2 and p < 0.01, respectively).

Univariate and multivariate analyses were also performed on patients without thrombocytopenia. Several significant covariates highlighted in previous prognostic models were identified, including the following:

- Age >65 years

- White blood cells >25 × 109/L

- Hemoglobin <10 g/dL

- Very high-risk karyotype

- Albumin <4.3 g/dL

- Mutations in ASXL, SRSF2, and RUNX1

- Presence of ≥2 high molecular risk mutations

All data were then collated and used to create a three-tiered prognostic system in the thrombocytopenic cohort, with the following scoring:

- Albumin <4.3 g/dL = 1 point

- SRSF2 mutation = 1 point

- TP53 mutation = 2 points

Individual patient scores were calculated and corresponded to their associated risk; 0, 1, and 2–3 points indicated low-, intermediate-, and high-risk, respectively. The median OS of the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups was 93.5 months, 29.5 months, and 7.2 months, respectively (p < 0.01). Low-risk patients accounted for 30% of the study population and had a similar OS to non-thrombocytopenic patients (93.5 months vs 80 months, respectively).

Conclusion

This study by Kuykendall, et al.1 demonstrated that conventional prognostic risk factors associated with MF are less effective for patients with thrombocytopenia. Patient outcomes were instead influenced by serum albumin levels and SRSF2 and TP53 mutations. Any patients lacking any of these factors recorded a survival rate comparable to that of patients with preserved platelet counts. While the results have clinical relevance, external validation would further enhance the findings.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content