All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Educational theme | Systemic mastocytosis: Disease overview

Mastocytosis is a clonal, neoplastic, proliferative disease characterized by the overproduction of morphologically and immunophenotypically abnormal mast cells that accumulate in one or more organs. In their 2016 revision, the World Health Organization (WHO) considered mastocytosis to be a distinct disease category, rather than a subtype of myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN).1

Mast cells are found in many organs such as skin, liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract (GIT), bone, blood, and bone marrow (BM). Clinical manifestations of mastocytosis are heterogeneous, and include mast cell activation syndrome, skin involvement, organ dysfunction secondary to infiltration, and BM failure. Outcomes also vary among patients, ranging from minimal impact on survival and quality of life, to severe impairment and poor survival. Presence of oncogenic gain-of-function mutations in the KIT tyrosine kinase domain (commonly a substitution of valine with aspartate, KITD816V) is the most common (> 90%) characteristic among patients with mastocytosis, and is associated with proliferation, growth, survival, and oncogenic transformation of mast cells.2,3

Mastocytosis is divided into two main categories: cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), which is limited to the skin; whereas systemic mastocytosis (SM) involves multiple organs.3 Here, we focus on the pathogenesis, diagnostic criteria, and types of SM, including a summary of a presentation by Jason Gotlib at the 9th Annual Meeting of the Society of Hematologic Oncology (SOHO 2021).2

Clinical manifestations of SM

The clinical presentation of SM can involve a range of life-threatening events, including:

- skin lesions (such as urticaria pigmentosa)

- organ damage

- mediator symptoms (e.g., flushing abdominal pain, diarrhea, anaphylaxis)

- associated myeloid neoplasms such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), MPN, and MDS/MPN overlapping syndrome, including chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

Pathogenesis

Mast cells, hematopoietic progenitor cells, germs cells, melanocytes, and interstitial cells in the GIT express the type III receptor KIT, which plays a role in normal mast cell development, hematopoiesis, gametogenesis, melanogenesis, and the regulation of slow gastric waves.1 KITD816V mutations have been found in 90–95% of adult patients with SM.2 However, in pediatric patients, germline or acquired activating KIT mutations have been identified, and clinical manifestations are different. Whilst adults have persistent multiorgan involvement with a concurrent non-mast cell hematologic neoplasm, children exhibit disease which is limited to skin and regresses with age.1 TET2 and N-RAS mutations have also been shown to be associated with mastocytosis; however, the pathogenesis or any prognostic value has not yet been determined.1

Diagnosis

The standard diagnostic examination for SM is BM biopsy, which also permits detection of any second hematologic neoplasms. Tryptase, expressed by all mast cells, is considered the most sensitive immunohistochemical marker, and is therefore included in the diagnostic criteria. Abnormal CD25 expression on BM mast cells can also be recognized by immunohistochemistry.

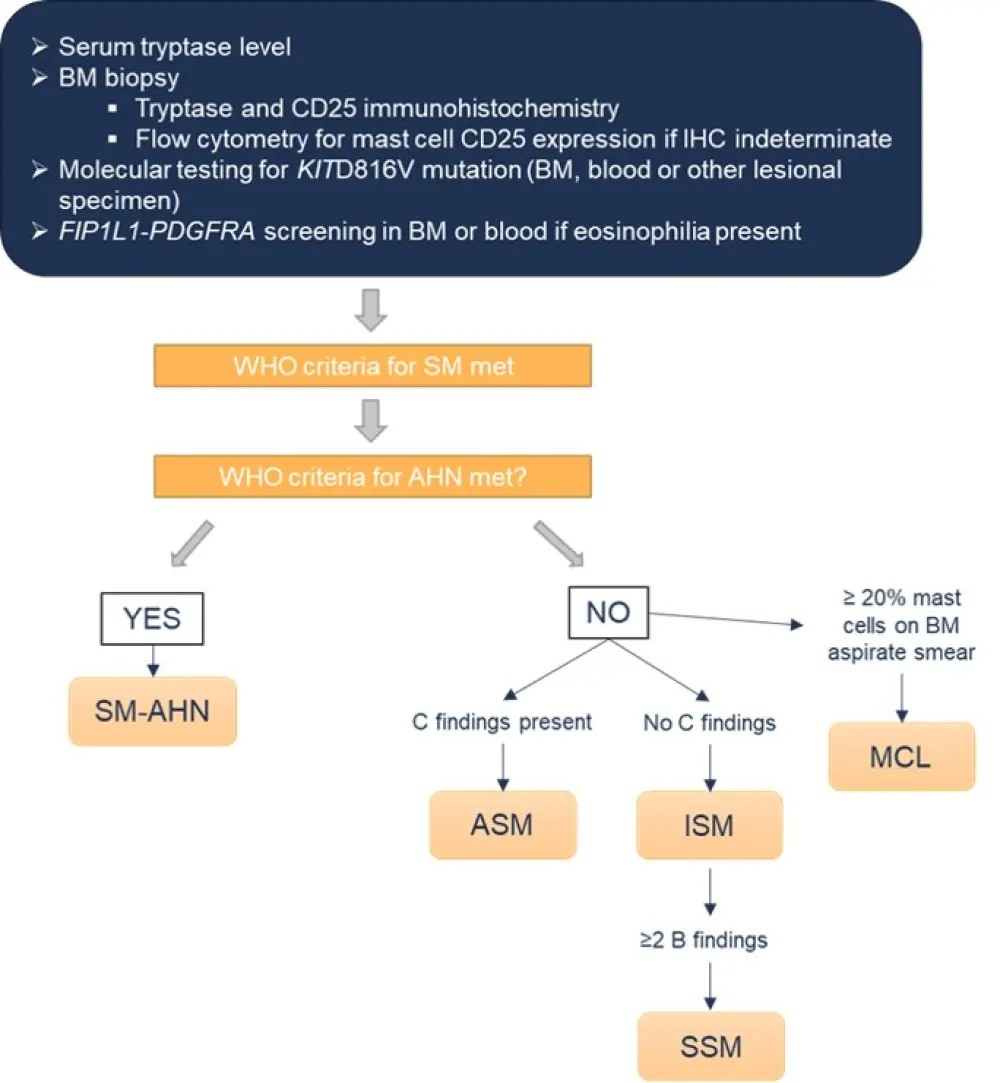

KIT mutations can be detected using a high-sensitivity assay (sensitivity ~0.01–0.1%), such as KITD816V allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or digital droplet PCR.2 However, molecular testing is considered a minor criterion for diagnosis (Figure 1).1 The MPN Hub has recently summarized a British Society for Haematology Good-Practice Paper on genetic testing in diagnosis and management of atypical MPN, including mastocytosis.

The diagnosis of SM requires the presence of one major and one minor criterion, or ≥3 minor criteria.2 Major and minor diagnostic criteria for SM, as identified by the WHO, are:

- Major criteria: mast cell aggregates (≥15) in BM or other extracutaneous tissue

- Minor criteria:

- presence of spindle-shaped mast cells

- KITD816V or other activating KIT mutation

- CD25 +/– CD2 expression on mast cells

- serum tryptase >20 ng/mL

Additional diagnostic refinements criteria (B and C findings) are also used as surrogates for disease volume and aggression (Table 1).2,3

Table 1. B and C findings in SM*

|

BM, bone marrow; SM, systemic mastocytosis. |

|

|

B findings |

C findings |

|---|---|

|

> 30% mast cells and tryptase level > 200 ng/mL in BM |

Cytopenias due to BM infiltration |

|

Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly without liver dysfunction or hypersplenism, or lymphadenopathy |

Liver dysfunction, ascites, and/or portal hypertension |

|

Signs of dysplasia or myeloproliferation, without an obvious associated hematologic disorder, with normal or mildly abnormal blood counts |

Large osteolytic and/or pathologic fractures |

|

Palpable splenomegaly with hypersplenism |

|

|

Malabsorption (hypoalbuminemia) with weight loss due to gastrointestinal mast cell infiltrates |

|

Types of SM

There are five types of SM (Table 2), and early determination of which is an important step prior to initiation of any treatment.1,2 An algorithm for SM diagnosis, as outlined in the 2016 WHO guidance, is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2. Types of SM*

|

BM, bone marrow; SM systemic mastocytosis. |

|||

|

SM type |

Criteria |

Proportion of patients affected |

Disease burden |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Indolent SM (ISM) |

0 or 1 B findings |

65% |

Lowest burden of disease and may not significantly affect survival, but patients may experience prominent symptoms |

|

Smoldering SM (SSM) |

≥ 2 or more B findings |

— |

Increased risk of progression to more advanced and damaging disease stage; considered a transitional stage between ISM and advanced SM |

|

Advanced SM |

— |

— |

Most aggressive, with poor survival and quality of life |

|

Aggressive SM (ASM) |

≥1 C findings |

~10% |

— |

|

SM with an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN) |

Presence of SM and a myeloid neoplasm |

~25% |

— |

|

Mast cell leukemia (MCL) |

≥20% mast cells on BM aspirate |

1% |

Median overall survival of patients of 2 months |

Figure 1. Diagnostic algorithm for SM*

AHN, associated hematologic neoplasm; ASM, aggressive SM; BM, bone marrow; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ISM, indolent SM; MCL, mast cell leukemia; SM; systemic mastocytosis; SSM, smoldering SM; WHO, World Health Organization.

*Adapted from Pardanani1

Treatment of SM

Treating adult patients with SM requires a greatly individualized approach, as covered in more detail in the second article within this Educational Theme. Traditional cytoreductive options include interferon, cladribine, and hydroxyurea. Symptom management is an important aspect for all patients, with some benefitting from allogeneic stem cell transplantation.1,3 The recent development of KIT inhibitors, such as midostaurin and avapritinib, have changed the therapeutic landscape and created the potential for more personalised treatment options.

Conclusion

Clonal proliferation of abnormal mast cells in one or more organ systems is a key characteristic of SM. Recent developments in treatment strategies for SM have prompted this Educational Theme, which also highlights the importance of risk stratification in informing treatment decisions.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content