All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Risk of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with MPN

Around 50% of patients with Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) report adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, and several studies have suggested a link between hematological cancers and the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

IBD is a term covering ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and is characterized by prolonged inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Chronic inflammation is also a hallmark of MPN and contributes to the symptom burden in both IBD and MPN. Studies have shown that patients with IBD are at a greater risk of developing hematological cancers, however the converse has not been investigated.

To date, no studies have determined the risk of IBD in patients with MPN, therefore Marie Bak and colleagues conducted a nationwide study, published in Cancers, to evaluate the risk of IBD in patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), myelofibrosis (MF), or unclassifiable MPN (MPN-U).1

Study design

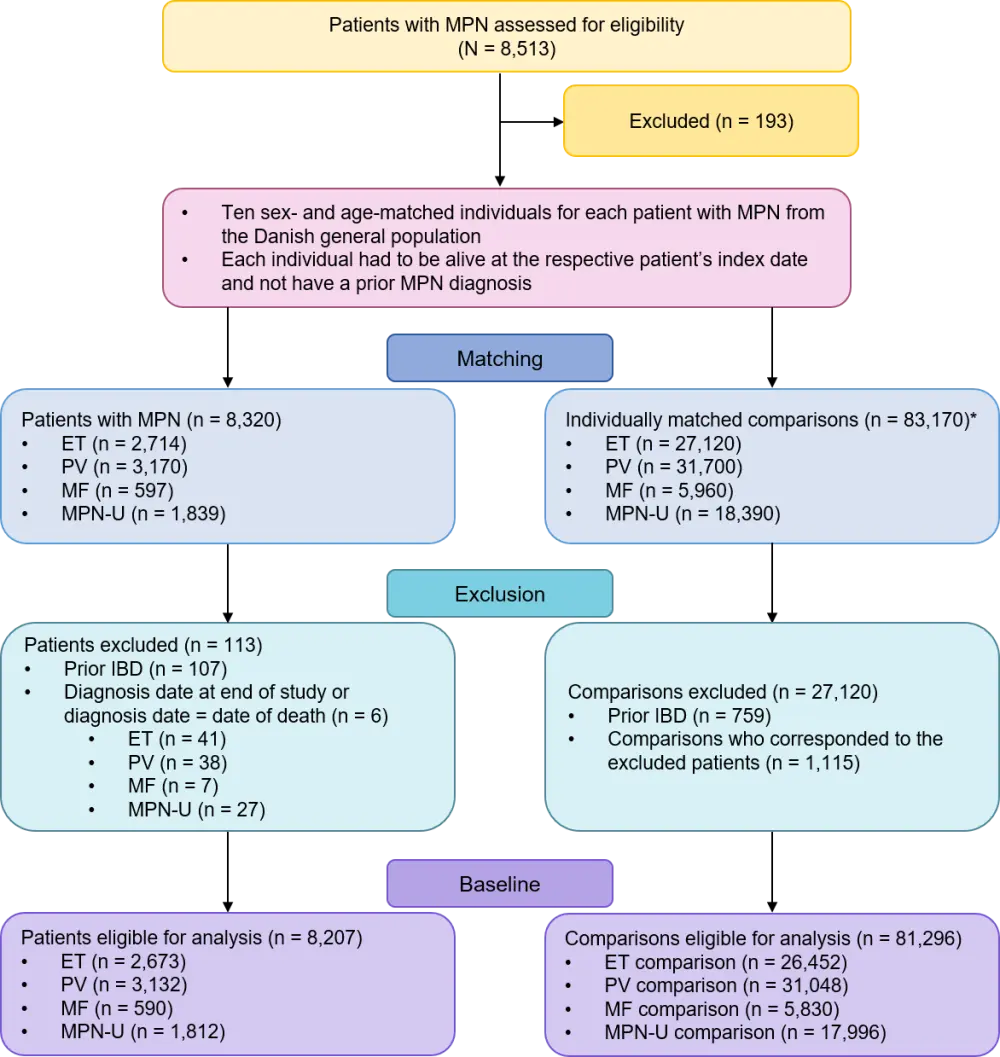

A nationwide, population-based cohort study to evaluate the risk of IBD in patients with MPN versus sex- and age-matched controls from the general population.

- The study evaluated patients aged ≥ 18 years on Danish registries with newly diagnosed ET, PV, MF, or MPN-U from 1994–2013 (Figure 1).

- Patients were matched 1:10 with sex- and age-matched comparisons, and both groups were evaluated from the index date until IBD diagnosis, death/emigration, or end of study (December 31, 2013).

Results

- Patients and comparisons were followed for 45,232 person-years, with a mean follow-up of 5.5 years.

- Of the evaluable population, 80 patients with MPN and 380 comparisons were diagnosed with IBD (Table 1).

- Rates of IBD per 1,000 person-years:

- MPN: 1.8 (95% CI, 1.4–2.2).

- Comparisons: 0.8 (95% CI, 0.7–0.8).

- The 1-, 3-, 6-, and 10-year risks of developing IBD are presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Patient and comparisons characteristics1

|

CD, Crohn’s disease; CI, confidence interval; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; UC, ulcerative colitis. |

||

|

Patients with MPN |

Comparisons |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Men |

3,780 |

37,454 |

|

Women |

4,427 |

43,842 |

|

Mean age at MPN diagnosis, years |

67.0 |

67.0 |

|

Risk time, years |

45,232 |

504,818 |

|

Mean follow-up, years |

5.5 |

6.2 |

|

Number of IBD events |

80 |

380 |

|

UC, % |

68.8 |

63.4 |

|

CD, % |

20 |

23.4 |

|

IBD rate per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) |

1.8 (1.4–2.2) |

0.8 (0.7–0.8) |

Table 2. Risk of IBD in patients with MPN and matched comparisons1

|

CI, confidence interval; ET, essential thrombocythemia; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; MPN-U, unclassifiable MPN; PV, polycythemia vera. *Patients with MF are included in the overall analysis, but the absolute risk is not shown for MF patients, as only one patient was diagnosed with IBD. |

|||||

|

Absolute risks of IBD |

MPN |

Comparisons |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n |

% (95% CI) |

n |

% (95% CI) |

||

|

MPN, total* |

1-year |

22 |

0.3 (0.2–0.4) |

49 |

0.1 (0.0–0.1) |

|

3-year |

35 |

0.4 (0.3–0.6) |

153 |

0.2 (0.2–0.2) |

|

|

6-year |

51 |

0.6 (0.5–0.8) |

255 |

0.3 (0.3–0.4) |

|

|

10-year |

65 |

0.8 (0.6–1.0) |

330 |

0.4 (0.4–0.5) |

|

|

ET |

1-year |

11 |

0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

17 |

0.1 (0.0–0.1) |

|

3-year |

19 |

0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

47 |

0.2 (0.1–0.2) |

|

|

6-year |

26 |

1.0 (0.6–1.4) |

85 |

0.3 (0.3–0.4) |

|

|

10-year |

28 |

1.0 (0.7–1.5) |

110 |

0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

|

|

PV

|

1-year |

4 |

0.1 (0.0–0.3) |

19 |

0.1 (0.0–0.1) |

|

3-year |

6 |

0.2 (0.1–0.4) |

67 |

0.2 (0.2–0.3) |

|

|

6-year |

11 |

0.4 (0.2–0.6) |

112 |

0.4 (0.3–0.4) |

|

|

10-year |

22 |

0.7 (0.4–1.0) |

138 |

0.4 (0.4–0.5) |

|

|

MPN-U |

1-year |

7 |

0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

11 |

0.1 (0.0–0.1) |

|

3-year |

9 |

0.5 (0.2–0.9) |

30 |

0.2 (0.1–0.2) |

|

|

6-year |

13 |

0.7 (0.4–1.2) |

45 |

0.3 (0.2–0.3) |

|

|

10-year |

14 |

0.8 (0.4–1.3) |

62 |

0.3 (0.3–0.4) |

|

- The risk of IBD was significantly greater in patients with MPN versus matched comparisons (Table 3).

- Patients with ET were at the highest risk for IBD, while risk rates were similar between patients with PV and MPN-U.

- Time since MPN diagnosis significantly influenced the risk of IBD.

- The risk of IBD was significantly greater within the first year (HR, 4.6; 95% CI, 2.8–7.6) and > 5 years following MPN diagnosis (HR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.1–4.2).

- The risk of IBD was not significantly greater in years 1–5 following diagnosis when compared with matched controls.

- Rates of prior IBD were significantly higher in patients with MPN compared with matched controls (odds ratio, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.7).

Table 3. HRs for IBD risk in patients with MPN compared with matched comparisons1

|

CD, Crohn’s disease; CI, confidence interval; ET, essential thrombocythemia; HR, hazard ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; MPN-U, unclassifiable MPN; PV, polycythaemia vera; UC, ulcerative colitis. |

||||||

|

Risk of IBD, crude HRs (95% CI) |

Events, n |

MPN |

ET |

PV |

MPN-U |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patients |

Comparisons |

|||||

|

IBD |

80 |

380 |

2.4 (2.1–2.9) |

2.8 (2.1–3.7) |

2.1 (1.6–2.7) |

2.2 (1.3–3.7) |

|

UC |

55 |

241 |

2.6 (2.1–3.2) |

3.0 (2.2–4.3) |

2.2 (1.6–3.1) |

1.7 (0.9–3.4) |

|

CD |

16 |

89 |

2.4 (1.7–3.4) |

3.2 (1.9–5.3) |

2.1 (1.2–3.6) |

1.6 (0.4–6.9) |

Conclusion

The findings from this study suggest that patients with MPN are at a greater than 2-fold higher risk of developing IBD and are 40% more likely to have a prior IBD diagnosis when compared with matched controls. This association might be explained by a shared pathomechanism. Therefore, the increased IBD risk should be kept in mind when evaluating abdominal symptoms in patients with MPN; while, in IBD patients, persistent leukocytosis and thrombocytosis may indicate concomitant MPN.

Limitations

- Symptoms of IBD are comparable to those of MPNs, as are treatment side effects. Therefore, IBD could have been disregarded or overlooked if no further tests were carried out.

- The risk of IBD was highest in the first year of MPN diagnosis, possibly because of detection bias leading to the overrepresentation of coincident IBD events during the diagnostic phase and clinical follow-up.

- Other potentially influential factors, such as smoking status, previous MPN treatments, and genetic profile, were not available, and therefore their impact on the risk of IBD could not be defined.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content