All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Survival outcomes following allo-HSCT in patients with accelerated phase myelofibrosis

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) is the only curative option for myelofibrosis (MF). Accelerated phase MF is defined as the presence of 10–19% circulating blasts and is associated with risk of leukemic transformation and poor outcomes; there is a lack of knowledge on the impact of transplant in accelerated phase MF.

At the 63rd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition, Nico Gagelmann et al.1 reported 5-year outcomes in patients with accelerated phase primary and secondary MF who underwent allo-HSCT, and the results have been recently published in Blood Advances.2 We summarize key results below.

Methods

In total, 349 patients with primary or secondary MF who underwent reduced intensity transplantation between 2004 and 2018 were included, with 35 characterized as having accelerated phase MF.2 Outcomes were compared with patients with circulating blasts <10% (chronic phase MF), and the effect of blasts on outcomes were evaluated.

Study endpoints included overall survival (OS, primary endpoint), relapse-free survival (RFS), nonrelapse mortality (NRM), and relapse incidence.

Prior to transplant, patients underwent a reduced intensity conditioning regimen consisting of busulfan-fludarabine (10 mg/kg bodyweight and 150 or 180 mg/m2, respectively), fludarabine-melphalan (150 mg/m2 and 140 mg/m2, respectively), and total body irradiation-fludarabine (150 mg/m2).

Results

Baseline characteristics for patients with chronic and accelerated phase MF are summarized in Table 1. Notable differences in the accelerated phase group included a higher median white blood cell (WBC) count (p = 0.08), a lower proportion of patients with Karnofsky performance status scale (KPS) <90% (p = 0.02), and a higher percentage of patients with constitutional symptoms (p = 0.10).

Table 1. Patient characteristics*

|

KPS, Karnofsky performance status scale; MF, myelofibrosis; WBC, white blood cell. |

||

|

Characteristic |

Chronic phase |

Accelerated phase |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age, years (range) |

58 (18–74) |

58 (39–72) |

|

Female, % |

41 |

37 |

|

Diagnosis, % |

||

|

Primary MF |

74 |

60 |

|

Secondary MF |

26 |

40 |

|

Median blasts, % (range) |

1 (0–8) |

14 (10–19) |

|

Median Hemoglobin, g/dl (range) |

9.6 (6.4–17.9) |

9.0 (6.1–13.2) |

|

WBC × 109/L, median (range) |

8.1 (0.6–168.8) |

13.6 (1.9–56.4) |

|

Platelets × 109/L, median (range) |

149 (6–2,437) |

115 (5–769) |

|

KPS†, % |

||

|

90–100% |

70 |

51 |

|

<90% |

30 |

49 |

|

Constitutional symptoms, % |

59 |

71 |

|

Cytogenetics, % |

||

|

Favorable |

79 |

80 |

|

Unfavorable |

10 |

10 |

|

Very high risk |

11 |

10 |

|

High molecular risk, % |

40 |

40 |

|

Number of mutations (range) |

2 (0–6) |

2 (1–4) |

Survival outcomes

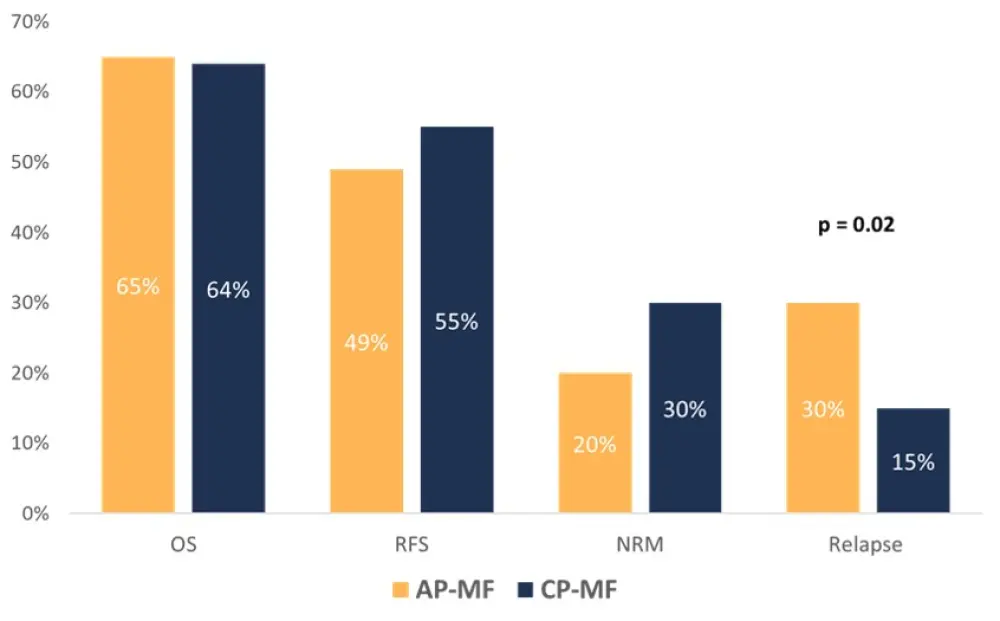

After a median follow up of 5.9 years, 5-year outcomes for OS, RFS, NRM and relapse are reported in Figure 1. In the accelerated phase cohort:

- the median OS was not reached

- the relapse rates were significantly higher (p = 0.02) with a median time to relapse of 1.4 years (vs 2.4 years with chronic phase; p = 0.46)

- estimated 5-year RFS was 49% with a median RFS of 4.8 years

Figure 1. 5-year OS, RFS, NRM, and relapse rates in patients with accelerated phase and chronic phase MF*

AP-MF, accelerated phase myelofibrosis; CP-MF, chronic phase myelofibrosis; NRM, nonrelapse mortality; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

*Data from Gagelmann et al.1,2

A longer follow-up of 10 years demonstrated an estimated median OS of 68% in the accelerated phase group. Other factors influencing OS included CALR/MPL-unmutated genotype, the presence of RAS mutations, KPS <90%, and age at transplantation (≥57 years).

In a multivariate analysis to evaluate the role of circulating blasts, there was no significant association between blast group with OS, RFS, and NRM. However, a higher circulating blast level was identified as an independent risk factor and associated with significantly increased risk of relapse (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.18–4.63; p = 0.02).

In a propensity matched analysis of patients with chronic and accelerated phase MF to account for selection bias, there was no significant difference between OS and RFS. Differences in NRM and relapse rates were not conclusive (p = 0.18 and p = 0.11, respectively). Relapse-related death seemed to be higher in the accelerated phase group (58% vs 10%; p = 0.03).

Finally, the investigators observed the entire spectrum of circulating blasts as a continuous variable and the effect on survival outcomes, genotype, and phenotypes. Median count of circulating blasts was 1% (0–19%). Higher circulating blasts correlated with lower hemoglobin levels (p = 0.04), higher WBC counts (p = 0.07), RAS mutations (p = 0.05), and constitutional symptoms at the time of transplantation. In terms of outcomes, higher circulating blasts was associated with increased risk of relapse (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99–1.11; p = 0.08) while having no impact on OS, RFS, or NRM.

Conclusion

Overall, this study demonstrated promising outcomes in patients with accelerated phase MF who undergo allo-HSCT, with OS and NRM comparable to patients with chronic phase MF. However, increased circulating blasts in this cohort presented a greater risk of relapse. More research into the effects of posttransplant therapies on relapse in this population are required to better understand how to mitigate this risk.

Study limitations reported by Gagelmann included the retrospective nature of the study, potential selection bias, and a center effect caused by differences in existing treatment or diagnostic techniques. This was controlled by limiting analysis to patients with similar conditioning regimens.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content