All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Trial updates for rusfertide (PTG-300) in polycythemia vera

For patients with polycythemia vera (PV), the current standard of care is periodic therapeutic phlebotomy (TP) with or without cytoreductive therapy to reduce the risk of thrombosis and PV-related erythropoiesis by maintaining hematocrit (HCT) levels <45% through iron depletion. However, iron deficiency and extensive erythropoiesis has been associated with suppression of hepcidin.

PTG-300, also known as rusfertide, is a novel injectable hepcidin mimetic which traps iron within macrophages via ferroportin inhibition, thus reducing iron exportation and availability in the circulation for erythropoiesis; and ultimately, increasing HCT levels.1,2 At the 63rd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition, results were presented from the phase II trials, PTG-300-041 and PTG-300-08,2 evaluating the ability of rusfertide to manage HCT levels in patients with PV. We summarize these presentations below.

PTG-300-041

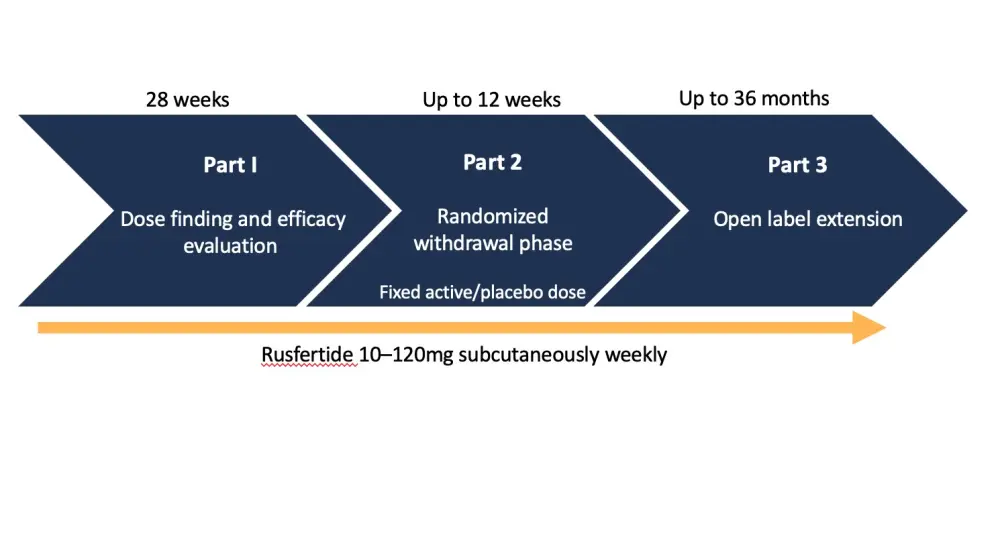

Ronald Hoffman presented 18-month results from the phase II PTG-300-04 trial (NCT04057040). The clinical goal for rusfertide, as an add-on therapy to standard of care, was to maintain HCT levels <45%. The study design is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study design*

*Adapted from Hoffman et al.1

The eligibility criteria for this study included:

- Phlebotomy-dependent PV diagnosis according to the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria

- ≥3 phlebotomies with or without concurrent cytoreductive therapy in the 24 weeks prior to enrollment

Patients were phlebotomized before the first dose of rusfertide to obtain standardized baseline HCT levels.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics*

|

PV, polycythemia vera; TP, therapeutic phlebotomy. |

|

|

Characteristic |

N = 63 |

|---|---|

|

Age, mean (range) |

56.3 (27–76) |

|

Male, % |

71.4 |

|

Risk, % |

|

|

Low |

44.4 |

|

High |

55.6 |

|

Therapy, % |

|

|

TP only |

49.2 |

|

TP + cytoreductive therapy |

50.8 |

|

Number of phlebotomies 28 weeks prior, % |

|

|

2–3 |

23.8 |

|

4–5 |

52.3 |

|

≥6 |

23.8 |

|

Days between phlebotomies, median |

35 |

Efficacy

In the first 28 weeks of treatment, the median dose of rusfertide was 40–60 mg/week. There was a dramatic reduction in number of phlebotomies in patients who received TP only or TP plus cytoreductive therapy. In total, 84% of patients did not require a phlebotomy, 14% required one, and 2% required two.

Very few patients had HCT levels >45% over three parts of the study. Concomitant reduction in red blood cell (RBC) counts was observed which was statistically significant, starting as early as Week 4 after treatment initiation (p < 0.01).

Rusfertide therapy normalized iron stores, as evident by a significant increase in serum ferritin levels by Week 4 (p < 0.01) that continually increased over the treatment course. Also, there was a significant increase in mean corpuscular volume (MCV) by Week 20 (p = 0.02) further increasing by Week 28 (p <0.01), and an increase in the percentage of transferrin saturation by Week 12 which was maintained by Week 28 (p < 0.01 for both).

The investigators also observed the effect of rusfertide on platelet and white blood cell (WBC) counts. On Week 4, there was significant increase in platelet count (p < 0.01) which persisted until Week 28 with a modest increase that did not exceed 20% in platelet numbers. By contrast, there was no increase in WBC counts throughout the treatment period.

Finally, the effect of rusfertide on symptoms was evaluated. Using patient myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN)-total symptom scores, there was a reduction from baseline to Week 28 (16.3 vs 11.4). Symptomatic reductions were most marked in the worst level of fatigue, and problems with concentration (p = 0.04)

Safety

A total of 55 patients (87%) experienced treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) but they were not attributed to rusfertide. Most drug-related adverse events were Grade 1 or 2. No Grade 4 or 5 events were reported. The most common events were injection site reactions (28.1% of injections). which were transient and did not lead to any discontinuation. One subject discontinued treatment due to asymptomatic thrombocytosis.

Notably, the PTG-300-04 trial was placed on clinical hold in September 2021 for 3 weeks by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), following non-clinical findings from a carcinogenicity study indicating two instances of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with rusfertide treatment. In the trial, one female patient aged 73 years old, with a history of SCC, developed SCC that was determined to be unrelated/possibly related to rusfertide therapy. Another male patient aged 65 years old transitioned into blast phase after 9 months into rusfertide therapy; this event was not related/possible related to rusfertide.

In summary, rusfertide therapy was associated with symptom improvement, and rapid and durable reduction in HCT levels below the target of 45%, without any increase in WBC counts or PV-associated thrombosis. It was found to be safe and well tolerated. The phase III trial will start enrolling patients in Quarter 1, 2022.

PTG-300-082

In the second presentation, Yelena Ginzburg presented another phase II study (NCT04767802) evaluating rusfertide in the absence of maintenance phlebotomy for patients who had previous treatment which failed to control HCT.

Study design

In the initial phase, rusfertide was added to the subject's current therapy at a dose of 40 mg twice weekly. In the maintenance phase, defined as a decrease in HCT <45% for two consecutive visits, rusfertide dosage was modified at the physician’s discretion.

Eligibility for the trial included:

- PV diagnosis according to the WHO criteria

- Baseline HCT >48% and history of ≥3 HCT values >48% in the year prior to enrolment

- High-risk or low-risk patients treated with TP with or without cytoreductive therapy

Twenty patients were enrolled, and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Patient characteristics*

|

HU, hydroxyurea; PV, polycythemia vera; TP, therapeutic phlebotomy. |

|

|

Characteristic |

N = 20 |

|---|---|

|

Aged > 60 years, % |

35 |

|

Female, % |

25 |

|

Low-risk PV, % |

65 |

|

Number of phlebotomies in prior 28 weeks |

|

|

0 |

35 |

|

1–2 |

45 |

|

3–4 |

15 |

|

≥5 |

5 |

|

Concurrent therapy, % |

|

|

TP alone |

20 |

|

TP + HU |

80 |

Efficacy

No phlebotomies followed the initiation of rusfertide even though not all patients achieved HCT <45% by Week 4. The data presented focused between Week 12–16, which was part of the initiation phase of rusfertide treatment in the absence of TP.

Rusfertide led to immediate HCT control with all patients exhibiting HCT <45% at Week 12 (p < 0.01). There was an oscillation in the percentage of patients with HCT <45% after Week 12 which was related to dose changes at the investigator’s discretion, with dosing intervals commonly decreased. Furthermore, the RBC count was significantly and continually decreased after 4 weeks (p < 0.01).

In line with results from the PTG-300-04 trial, there was again a normalization of iron stores, with ferritin levels increased significantly by Week 4 (p < 0.01). Meanwhile, the percentage of transferrin saturation rapidly increased by Week 4 (p = 0.02); however, this increase was transient with no significant difference from initiation by Week 16 (p = 0.51). MCV was also increased by Week 4 (p < 0.01), with Ginzburg suggesting that erythroblasts which express ferroportin, were unable to export iron in high hepcidin states.

Rusfertide treatment led to a continual increase in WBC counts which was significant by Week 4 (mean increase of 12.5 to 13.7 × 109/L; p = 0.04), and Week 16 (p < 0.01). Platelet count was also increased by Week 4 (mean increase of 483 to 765 × 103/L; p <0.01), and maintained on Week 16 (p = 0.02). A total of 60% of patients were reported to have more than a 50% increase in platelet counts from baseline.

Safety

In total, 13/20 patients (65%) experienced a TEAE. Similar to the PTG-300-04 trial, most treatment-related AEs were mostly Grade 1 or 2. There was one instance of treatment discontinuation resulting from Grade 4 thrombocytosis without bleeding or thrombosis. Again, injection site reactions were the most observed adverse events, occurring in 68% of injections. However, these were transient, and no patient discontinuation occurred. No anti-drug antibody response was recorded.

In summary, rusfertide therapy alone achieved rapid control of HCT in erythrocytic patients with PV. Following initial HCT control, there was a successful transition from an initial twice weekly dosage to maintenance dosage occurring weekly. Ginzburg highlighted that the effects of increased platelet and WBC counts are to be further evaluated in a larger cohort in a longer follow-up.

Conclusions

Evident from data presented in the clinical setting, rusfertide provides rapid control of HCT in patients with PV, reducing both the number of phlebotomies given and maintaining HCT <45% in the absence of TP. Rusfertide may provide a novel therapeutic alternative for patients unwilling or unable to receive maintenance TP. However, further evaluation on the effect of raised WBC and platelet counts is required.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content