All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

A real-world study of predictors of response to HU and switch to ruxolitinib in patients with PV

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a Philadelphia-negative chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) characterized by clonal expansion of erythrocytes.1 This leads to thrombotic complications and the risk of progression to post-PV myelofibrosis or blast phase.1

Currently, hydroxyurea (HU) is the most used cytoreductive therapy, but it is associated with poor responses and toxicity in a significant proportion of patients. Moreover, the predictors of a complete response (CR) with HU and its prognostic implications are yet to be defined.1 The impact of different types of suboptimal responses in patients switching to ruxolitinib (RUX) is also unclear.1

Palandri et al.1 recently published in Cancers, a real-world, retrospective study (PV-NET) identifying factors associated with CR during HU treatment, along with whether the type of HU responses would influence a patient’s decision to switch to RUX. The MPN Hub is pleased to summarize the key findings here.

Study design

This is an observational, retrospective cohort study across 22 hematologic centers. A total of 563 patients diagnosed with PV according to the World Health Organization 2016 definition between 1985 and 2000 and treated with HU for ≥12 months were included.

Results

Efficacy

- HU was administered as a front-line therapy in 98.1% of patients, with 87.6% receiving it due to high-risk criteria.

- The median duration of HU exposure was 4.6 years.

- The median dose of HU was 0.5 g/d with 31.6% of patients receiving a median dose of ≥1 g/d.

- Patient characteristics are highlighted in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics*

|

HU, hydroxyurea. *Adapted from Palandri, et al.1 †548 evaluable patients. ‡506 evaluable patients. |

|||

|

Characteristics |

Complete responders (n = 166) |

Poor responders (n = 397) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Median age (range), years |

70 (47–87) |

65 (21–89) |

<0.001 |

|

Sex, male (%) |

39.8 |

55.4 |

0.001 |

|

Median platelet count (range), ×109/L |

500 (159–1279) |

449 (138–1209) |

0.004 |

|

Median leukocyte count (range), ×109/L |

10 (3.3–30.3) |

10.1 (1–27.3) |

0.70 |

|

Median hemoglobin (range), g/dL |

|||

|

Male |

18.6 (15.8–23.6) |

18.7(12–23.4) |

0.59 |

|

Female |

17.8 (15.3–22) |

17.5 (13.2–21.9) |

0.09 |

|

Median hematocrit (range), % |

|||

|

Male |

55 (48.9–72.5) |

56.3 (38–73) |

0.70 |

|

Female |

54 (47.6–71.7) |

54.1 (39–72) |

0.99 |

|

Palpable spleen†, % |

15.8 |

39.4 |

<0.001 |

|

Pruritus, % |

17 |

39.9 |

<0.001 |

|

Thromboses pre-/at diagnosis, % |

23.5 |

25.7 |

0.58 |

|

Median HU dose‡ (range), g/d |

0.8 (0.2–2) |

0.5 (0.2–2) |

<0.001 |

|

Median HU dose ≥1 g/d, g/d |

49.6 |

26.17 |

<0.001 |

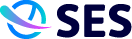

- Poor response to HU was experienced by 70.5% of patients, while 29.5% of patients experienced CR (Figure 1).

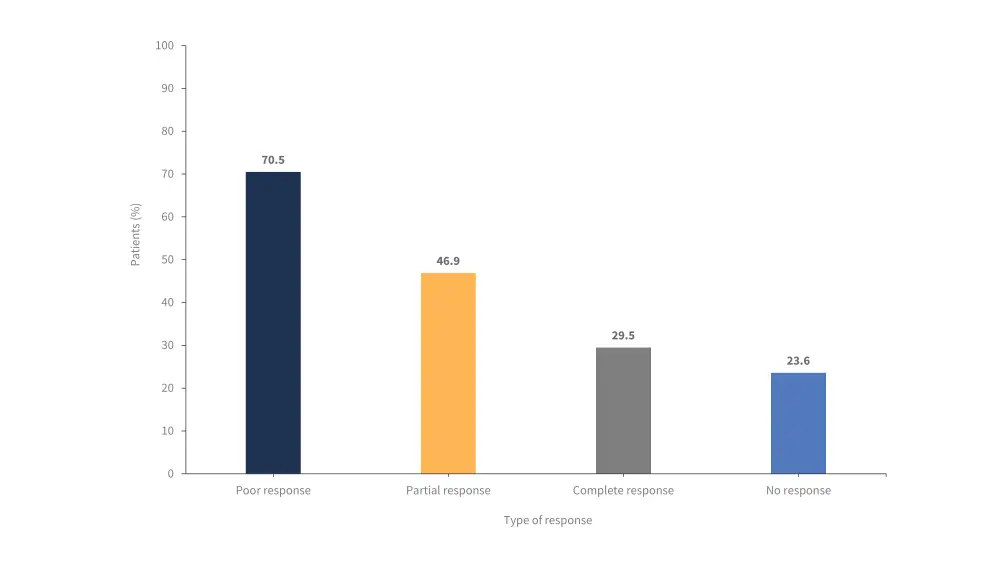

- Of the patients who experienced a poor response to HU, 66.5% experienced a partial response and 33.5% no response (Figure 2).

- A variant allele frequency of <50%, along with an absence of a palpable spleen (p = 0.05), and patients who received a median dose of HU ≥1 g/d (p = 0.05) were associated with CR.

- In the multivariate analysis, several factors were significantly associated with CR; these were:

- Absence of pruritus (odds ratio [OR], 3.23; p = 0.002)

- Absence of palpable splenomegaly (OR, 2.31; p = 0.03)

- A median HU dose of ≥1 g/d (OR, 4.69; p < 0.001)

Figure 1. Response rates in patients treated with HU*

*Adapted from Palandri, et al.1

Figure 2. A) Response rates of patients who experienced a poor response to HU; B) Percentage of patients who experienced a poor response to HU who either remained on HU or switched to RUX*

HU-POOR, patients who experienced a poor response and remained on hydroxyurea; HU-RUX, patients who switched from hydroxyurea to ruxolitinib; NR, no response; PR, partial response.

*Adapted from Palandri, et al.1

Safety

- At least one treatment-related adverse event (TRAE) of Grade ≥2 was experienced by 22.7% of patients.

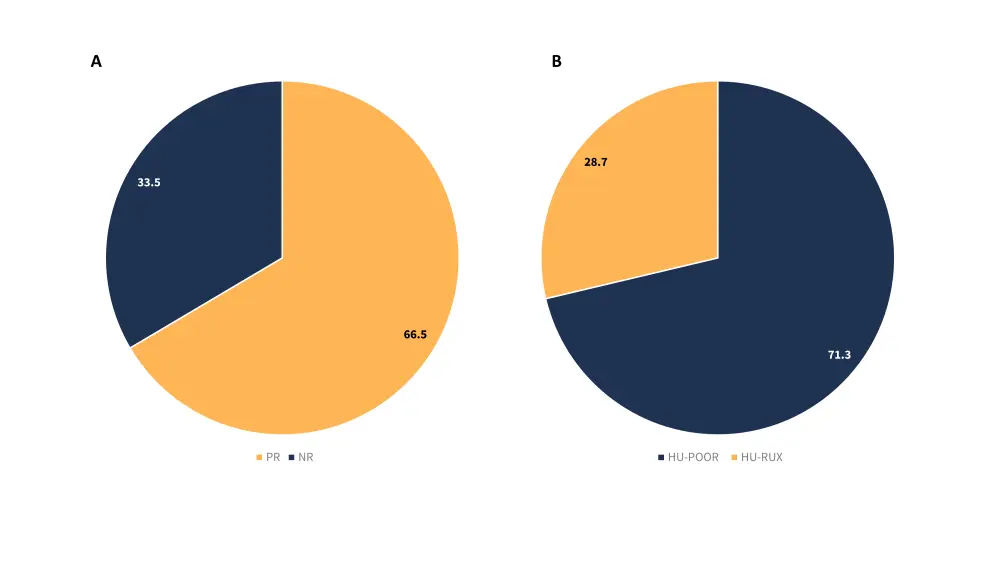

- An increased incidence of overall adverse events (p = 0.002), anemia (p = 0.03), and skin ulcers (p = 0.02) were associated with a dose ≥ 1g/d (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Adverse events according to HU dose*

AE, adverse event; HU, hydroxyurea.

*Adapted from Palandri, et al.1

Treatment approach for poor responders

- Among the poor responders, 28.7% of patients switched to RUX and the remaining 71.3% continued treatment with HU. Of the patients switching to RUX:

- 43.8% of patients discontinued HU treatment due to toxicity.

- 21% switched within 12 months.

- 79% switched after 12 months from index date.

- The median duration of exposure to RUX was 1.5 years.

- Patients who switched from HU to RUX were significantly more likely to be younger (p<0.001).

- These patients also showed a higher likelihood of having a palpable spleen (p = 0.004) and pruritus (p < 0.001).

- After 5 years, the probability of patients switching to RUX was significantly higher in patients with hematolytic and spleen/symptom criteria (p < 0.001).

- Patients with no response also had a higher probability of switching to RUX compared with those who had partial response (p < 0.001).

- Multivariable analysis showed splenomegaly was associated with an early switch from HU to RUX (p = 0.04).

- Other factors associated with a late switch from HU to RUX included need for phlebotomy (p = 0.01), median dose of HU ≥1 g/d (p < 0.001), and pruritus (p < 0.001).

Clinical outcomes based on response to HU

- Among the 449 patients receiving only HU, 51 thrombotic events, 25 hemorrhagic events, and 43 infections were recorded.

- 52 patients developed a secondary primary malignancy, 14 patients progressed to post-PV myelofibrosis, 10 progressed to blast phase, and death was reported in 35 patients.

- Achieving a response defined by European LeukemiaNet with HU was not associated with a reduced risk of thrombosis (p = 0.86), decreased risk of disease progression (p = 0.9), or reduced risk of death (p = 0.86).

- However, prior thrombotic events were associated with subsequent thrombotic events (p = 0.01).

- An age of ≥65 years was associated with an increased mortality risk (p = 0.02).

Conclusion

This real-world, retrospective cohort study highlights the importance of optimizing HU dosing. Although higher HU dosing achieves greater rates of CR it also increases the risk of TRAEs. In addition, the study also demonstrates the lack of an association between CR and reduced thrombotic risk. Therefore, HU dosing should be determined based on individual patient needs. Furthermore, a large proportion of stable poor responders continued HU treatment, emphasizing the need to improve overall therapeutic strategy. However, due to the retrospective nature, this study was limited by factors such as patient selection, uncontrolled drug prescription, inadequate recognition of poor response to HU, and inadequate drug compliance assessment.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content