All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Advances in allogeneic HSCT for patients with myelofibrosis

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is the only potentially curative treatment for patients with myelofibrosis (MF), and both its potential and drawbacks have been discussed widely during the Virtual Edition of the 46th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Nicolaus Kröger gave a detailed talk about allo-HSCT in MF, while Jean-Baptiste Bossard et al., Juan Carlos Hernandez-Boluda et al., and Isik Kaygusuz Atagunduz et al. presented results from different studies investigating allo-HSCT.

In this review, we will explore the use of allo-HSCT in treating patients with MF, by providing updated information on a recently developed transplant-risk scoring system for myelofibrosis,1,2 the impact of splenectomy on allo-HSCT outcome,3 key factors effecting posttransplant survival,4 and the risk of late relapse after allo-HSCT.5

Allo-HSCT for the treatment of MF1

In his overview presentation, Nicolaus Kröger explained that, a few decades ago, allo-HSCT was not considered standard of care due to the high rate of treatment-related mortality. However, the picture has changed over the years. Recent studies have shown that cure rates can reach up to 70%, especially for younger patients (≤ 55 years of age) that have a matched (related or unrelated) donor. Allo-HSCT has been associated with rapid resolution of bone marrow fibrosis and almost complete resolution of osteosclerosis. Favorable results have led to more common use of allo-HSCT; interestingly, the number of patients who underwent allo-HSCT in Europe has doubled since 2006.

In a study conducted by Daghia et al.,6 reduced-intensity allo-HSCT in patients aged > 65–74 years with advanced myelofibrosis have shown:

- Non-relapse mortality (NRM) rate of 21% at 1-year post-transplant

- Relapse rate of 10%

- 10-year overall survival (OS) of 68%, and even higher OS of 73% with good performance status

The Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System

The mortality risk needs to be considered in the context of allo-HSCT, and the Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System (DIPSS) for primary MF is a frequently used tool for risk scoring using age, constitutional symptoms, hemoglobin, leukocytes, and blood blast levels. Risk groups are defined as low, intermediate-1, intermediate-2, and high, based on these parameters. Estimated median OS for high risk disease is around 2 years, while this can increase to 15 years for intermediate-risk disease.

As reported by Kröger, patients in the low and intermediate-1 risk groups seem to have significantly better outcomes with non-transplant therapies; the survival outcome for the intermediate-2 and high-risk group was better with allo-HSCT (p = 0.005 and p = 0.0005, respectively). For more data on survival following allo-HSCT, read here.

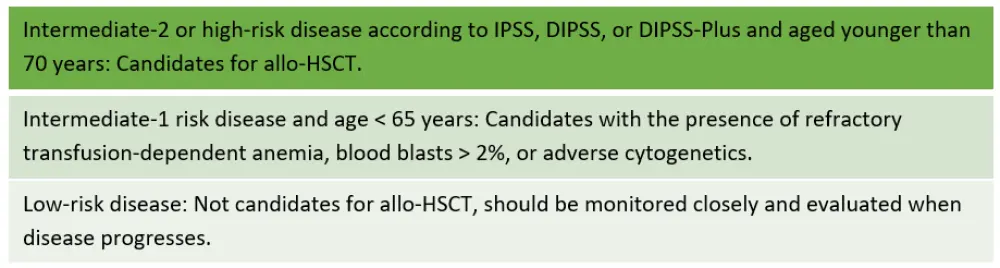

Another study suggested that patients with intermediate-1 risk disease may benefit at a later course of disease. The treatment guidelines are in line with these findings, and the EBMT/European LeukemiaNet (ELN) recommendations for selecting patients who benefit from allo-HSCT are detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. EBMT/ELN recommendations1

Myelofibrosis Transplant Scoring System1

The myelofibrosis transplant scoring system (MTSS) is a clinical–molecular scoring system, developed by Nico Gagelmann et al. in 20192 to predict outcomes in patients with primary or secondary MF undergoing allo-HSCT. This scoring system is based on patient-, disease-, and transplant-specific risk factors (Table 1).

Table 1. Parameters in MTSS1

|

MTSS, myelofibrosis transplant scoring system; PS, performance status. |

|

|

Parameter |

Score |

|---|---|

|

Age > 57 years |

1 |

|

Karnofsky PS ≤ 90 |

1 |

|

Leukocyte count > 25 × 109/L |

1 |

|

Platelet count ≤ 150 × 109/L |

1 |

|

CALR + MPL unmutated genotype |

2 |

|

ASXL1 mutation |

1 |

|

Mismatched unrelated donor |

2 |

Based on these parameters, risk groups and estimated OS and NRM for each risk group were defined as in Table 2.

Table 2. Risk groups in MTSS and related outcomes1

|

MTSS, myelofibrosis transplant scoring system; NRM, non-relapse mortality; OS, overall survival. |

|||

|

Score |

Risk group |

5-year OS, % |

NRM, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

0–2 |

Low risk |

90 |

10 |

|

3–4 |

Intermediate |

77 |

22 |

|

5 |

High |

50 |

36 |

|

≥ 6 |

Very high |

34 |

57 |

For an optimized transplantation procedure, the type of donor source (i.e., matched/mismatched, related/unrelated) is considered an important factor for improved outcomes. Before allo-HSCT, reducing iron overload by chelation and using a JAK inhibitor to reduce constitutional symptoms and spleen size can be considered. An appropriate conditioning regimen can be selected based on age, disease status, and comorbidities. Post transplantation, prophylactic therapy for graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), monitoring minimal residual disease, and early discontinuation of immunosuppressive agents to prevent relapse can be considered.

Impact of splenectomy on allo-HSCT outcome3

Jean-Baptiste Bossard et al. retrospectively investigated whether performing splenectomy prior to allo-HSCT would impact transplantations or death rates in 530 patients with MF.

The study concluded that there was no significant association between splenectomy and death rate following transplant. Furthermore, data suggested that most patients underwent splenectomy as preparation within the first 4 months prior to transplantation. These findings indicated that splenectomy may be safely considered before transplantation.

Factors effecting post-transplant survival4

In another study conducted by the Chronic Malignancies Working Party of the EBMT, Juan Carlos Hernandez-Boluda et al. investigated the key factors of survival in patients with MF undergoing allo-HSCT, laying emphasis on the prognostic value of events occurring after transplant, and identified predictive factors leading to posttransplant complications. They evaluated nearly 3,000 patients with MF who had allo-HSCT with an HLA-identical sibling or unrelated donor, and at a median follow-up of 4.7 years, almost half of patients (47%) had died. The causes of death included relapse, GvHD, infection, and organ failure.

Factors considered to be associated with higher mortality rate included:

- Age ≥ 60 years

- Karnofsky performance status below 90% at the time of transplant

- Graft failure

- Grade III–IV GvHD

- Disease progression and/or relapse during follow-up

Patients transplanted from an unrelated donor had an increased risk of graft failure and were at higher risk for Grade III–IV acute GvHD. While risk of progression or relapse appeared to be greater with intermediate-2 risk or high-risk disease based on DIPSS categories, it tended to be lower in patients with a CALR mutation. In addition, there was no association between previous ruxolitinib treatment and the risk of graft failure, Grade III-IV acute GvHD, relapse, and NRM.

Post-transplant relapse5

Isik Kaygusuz Atagun et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in 94 patients with MF to evaluate relapse rates after a 5-year follow-up. They analyzed disease-related characteristics and outcomes of patients with late relapse, defined as relapse after 5 years, in a longer follow-up duration.

- 12% of patients had late relapses at a median of 7.1 years (n = 13).

- 88% experienced no relapse at a median follow-up of 8.76 years (n = 81).

Median time from diagnosis to allo-HSCT was found to have no impact on relapse. Other parameters, including cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities, type of allo-HSCT or conditioning regimens, molecular complete remission following allo-HSCT, development of acute or chronic GvHD, blast counts prior to transplant, or degree of bone marrow fibrosis at the time of transplant were not associated with a significantly greater risk of late relapse.

In the group of patients with relapses, 11 patients were still alive at the time of analysis. The causes of the two death events in relapsing patients were secondary malignancy (n = 1) and disease progression (n = 1). Relapsed patients were treated with donor lymphocyte infusion with different number of doses and/or second allo-HSCT. These approaches led to full donor cell chimerism and molecular remission in 72.7% of patients.

Conclusion

The clinical value of allo-HSCT is significant for certain patients with MF. It is important to identify those patients who may be good candidates with the help of risk scoring systems, such as DIPSS or MTSS. Taking into account factors which may increase the risk of post-transplant complications, such as age, performance status, severe GvHD, and graft failure, will help to inform treatment decisions. Although relatively low and late, the risk of relapse is still considered an issue following allo-HSCT, highlighting the importance of monitoring after transplant and the use of donor lymphocyte infusion and second transplant to re-induce remission.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content