All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Novel approaches to reduce inflammation in myeloproliferative neoplasms

Do you know... The drug N-acetylcysteine has been suggested as a low-cost approach to reduce inflammation in MPN. Which biological molecule is significantly reduced during treatment?

Patients diagnosed with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) have notably elevated levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF‑α).1 Each MPN subtype has a distinct inflammatory signature which is thought to contribute to overall symptom causation, anemia, and an increased risk of thrombosis.

It remains unclear as to what drives inflammation in MPN; however, it has been shown that the MPN clone itself magnifies the pro-inflammatory environment and that chronic inflammation may predate the beginnings of MPN and could also contribute to an increased risk of developing the disease.1

During the 1st Congress on Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Controversies and Debates, Fleischman gave a presentation on low-risk and low-cost approaches to reducing MPN-related inflammation.1 The approaches included treatment with N-acetylcysteine, altering the gut microbiome, and optimizing diet. Here, we are pleased to provide a summary of this presentation.

N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine is an antioxidant suggested to play a role in preventing cancer. In patients with MPN, it has been shown to reduce TNF‑α levels in both normal and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as well as extending the overall survival time of JAK2V617F knock-in mice. The mouse model study also highlighted a protective effect of N-acetylcysteine on wild-type mice from induced thrombosis.

UCI 20‑50 study

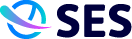

The UCI 20‑50 study is an ongoing optimal dose finding study for the use of N-acetylcysteine in patients with MPN. The study utilizes a standard simple toxicity and efficacy interval design for seamless phase I/II clinical trials (Figure 1) and is currently in the recruitment phase. The measure of efficacy is a 30% reduction in symptom burden.

Figure 1. UCI 20-50 study design*

BID, twice daily; CBC, complete blood count; CMP, comprehensive metabolic panel; IFNα, interferon alpha; JAK, Janus kinase inhibitor; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; TSS, total symptom score; w/diff, with differential.

*Adapted from Fleischman.1

Gut microbiome

A recent study investigated the makeup of the gut microbiome in patients with MPN compared with the overall population and found no significant difference in species richness between the two patient groups. However, there were significantly lower levels of phascolarctobacterium in patients with MPN. At normal levels, this species of bacteria is associated with reduced inflammation and lower levels of C‑reactive protein. Moreover, it is a producer of propionate, a short chain fatty acid that inhibits pro‑inflammatory cascades, resulting in the suppression of the pro-inflammatory regulator, nuclear factor kappa B. In contrast, during colonic inflammation, levels of this bacterium are reduced. Collectively, the study revealed that an MPN diagnosis accounts for only a 1.7% difference in microbiome variance between patients with MPN and those in a healthy population. Furthermore, patients with the MPN subtype polycythemia vera had a lower distribution of species abundance compared with the control group. The composition of gut microbiome was also found to differ depending on the treatment regimen, with interferon alpha treatment being most similar to that of the control group. Overall, only subtle differences were observed, and further studies are needed to investigate whether differences are a consequence of MPN or a change in response to treatment.

Diet

The Mediterranean diet (high in whole grains, vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, seeds, herbs, and spices) is regularly associated with anti-inflammatory effects, as well as being beneficial in patients with metabolic disease. A Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil or nuts has been shown to reduce levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6. The diet is high in fiber, antioxidants, and monounsaturated fats, and has therefore been suggested as a tool to reduce inflammatory cytokine levels in patients with MPN. This could also help to relieve symptom burden and slow disease progression.

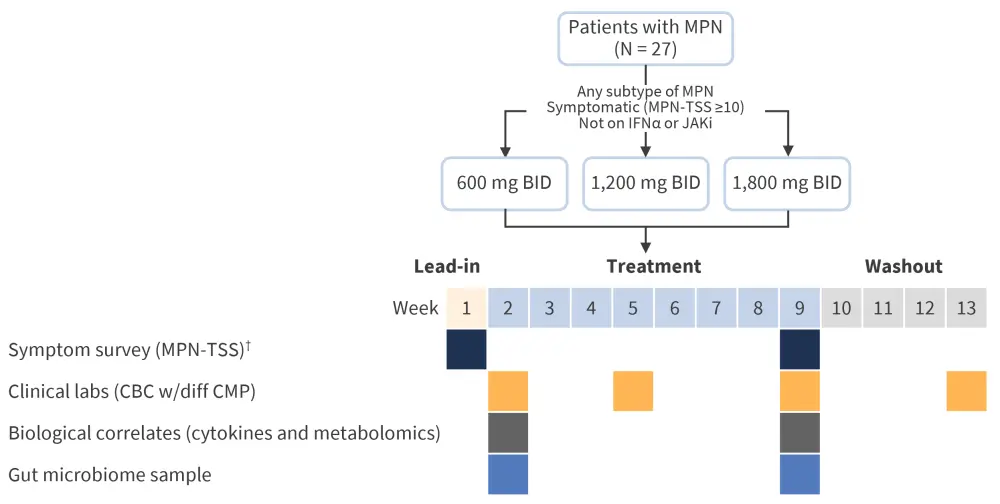

Two feasibility studies have recently been completed at the University of California Irvine, aiming to assess the likelihood of patients being able to adopt the proposed changes in diet. The initial pilot study (Figure 2) enrolled a total of 30 patients with MPN and investigated a Mediterranean diet compared with a United States Department of Agriculture diet. Patients received in-person dietician counselling and a weekly curriculum sent via email.

Figure 2. Diet intervention pilot study design*

ASA24, Automated Self-Administered 24-hour Dietary Assessment Tool; CBC, complete blood count; CMP, comprehensive metabolic panel; hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein test; MED, Mediterranean; USDA, United States Department of Agriculture.

*Adapted from Fleischman.1

†Biological samples consisted of blood draw, CBC, CMP, lipid panel, hsCRP, plasma for cytokine analysis, and stool sample.

‡Provisions consisted of supplementation of diet with olive oil or being given a grocery card.

§Surveys consisted of ASA24, Mediterranean diet adherence questionnaire, feasibility questionnaire, and symptom surveys.

The results of the initial pilot study demonstrated the following:

- A total of 80% of patients could adapt to a Mediterranean diet pattern with consistent registered dietician counselling.

- There was a greater symptom burden reduction observed in the Mediterranean diet group.

- Although there were no significant changes in the gut microbiome, patients diagnosed with myelofibrosis had reduced microbial richness and evenness in both patient groups.

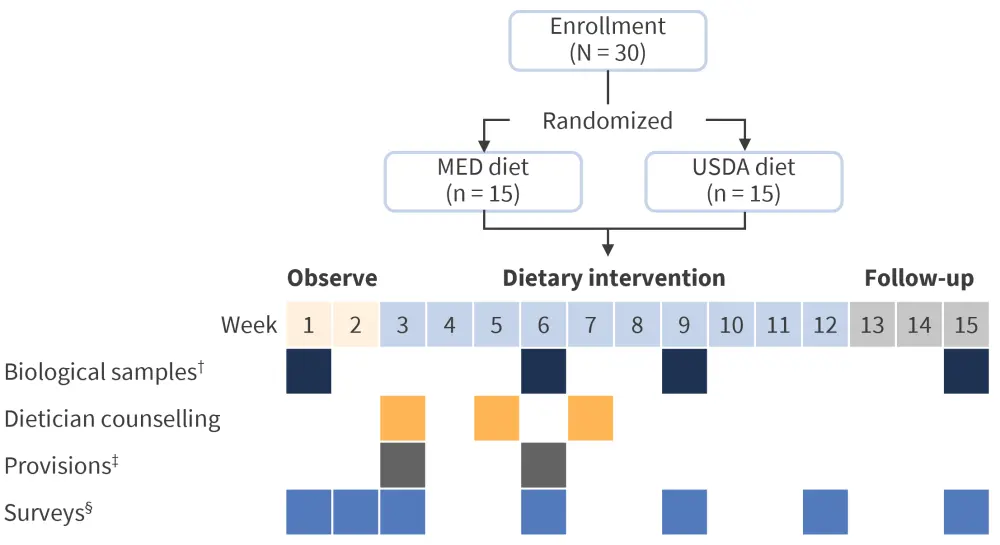

The second feasibility study (Figure 3) focused on whether patients with MPN could participate in fully online dietary studies.

Figure 3. e-Intervention study design*

DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; MED, Mediterranean.

*Adapted from Fleischman.1

The study found that while patients with MPN were eager to attend registered dietician Zoom counselling sessions and complete short daily surveys, a significant proportion had difficulty completing online 24-hour diet recalls. Larger online based interventions are required to detect changes in symptoms, as well to include standard of care for comparison. With regards to the Mediterranean diet itself, the addition of fermented foods should be considered to maximize any positive changes to the gut microbiome.

Conclusion

Patients with MPN show increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which is thought to contribute to the observed symptoms. Low-cost and low-risk approaches to counteract this are in increasing demand. N-acetylcysteine has been shown to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF‑α levels, while optimizing the gut microbiome. Therefore, switching to a Mediterranean diet could further aid in reducing overall inflammation and symptom burden.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content