All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Essential thrombocythemia: Disease and treatment overview

Do you know... What is the first-line of treatment for intermediate- and high-risk patients with ET?

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a chronic Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) disease subtype characterized by excessive proliferation of platelets, pronounced thrombosis, a high frequency of thrombotic events, and hemorrhagic risk.1 Compared with other MPN disease subtypes (myelofibrosis [MF], and polycythemia vera), ET has a favorable overall prognosis; however, the overall survival rate remains poor compared with the general population.1 Here, we provide an overview of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of ET.

Etiology

- Between 50–60% of patients harbor a mutation in the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) gene,2 with the JAK2V617F mutation being the most common.2

- Other common driver mutations include the myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene, present in around 3% of patients; and calreticulin (CALR), present in 15–32% of patients.2

- These mutations cause constituent activation of the JAK/signal transducers and activators of transcription and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways, as well as hypersensitivity to thrombopoietin, resulting in uncontrolled thrombocyte proliferation.2,3

- Risk factors include4:

- working in agriculture and petroleum refineries;

- benzene exposure; and

- smoking.

Epidemiology

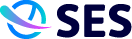

Figure 1. Essential thrombocythemia epidemiology*

*Data from Accurso, et al.1 and Li, et al.5

Pathophysiology6

- The common JAK2V617F mutation results from a valine-to-phenylalanine substitution at codon 617.

- Mutations in CALR are due to insertions or deletions resulting in a reading frame shift and the formation of a novel C-terminus.

- Point mutations in the myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene lead to hypersensitivity to the thrombopoietin receptor.

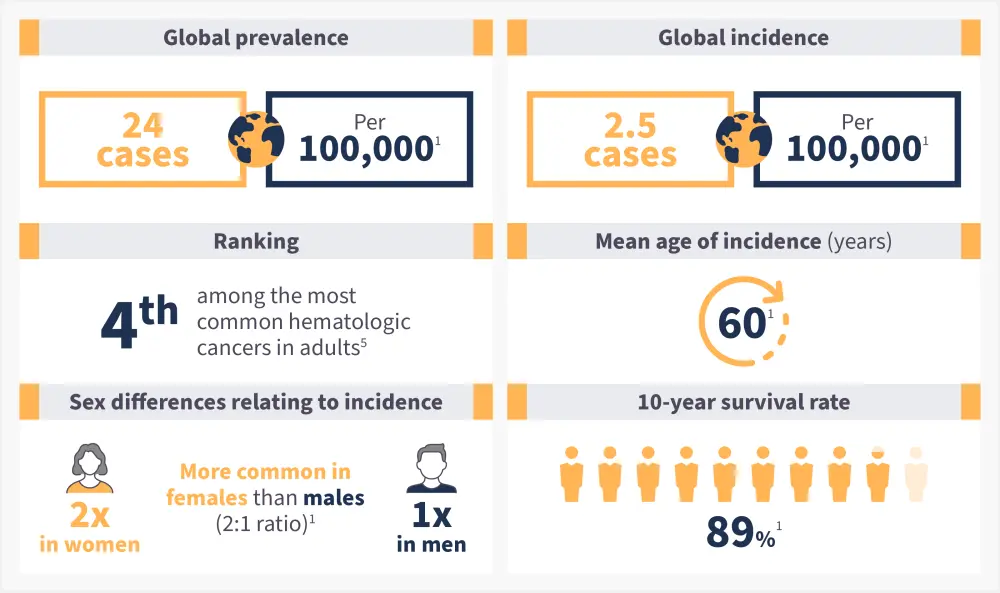

- The subsequent gain in function primarily affects the JAK2 mutation, activating signaling pathways associated with hematopoietic cytokine receptors including erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. (Figure 2).

This results in2:

- increased megakaryocyte mobility

- increased thrombocyte production

- deficiency of glycoprotein VI on the surface of platelets

- increased risk of thrombosis

Figure 2. Essential thrombocythemia pathophysiology*

JAK2, Janus kinase 2; RBC, red blood cell, TF, tissue factor.

*Adapted from Falchi, et al.10

Created with BioRender.com

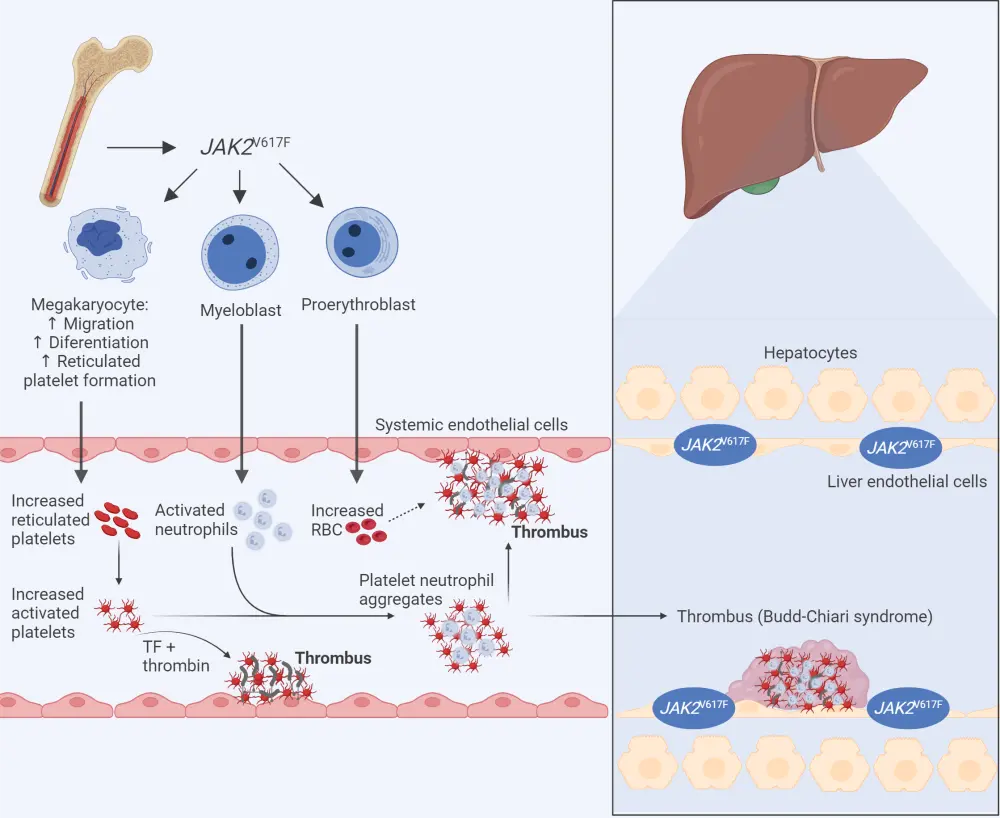

Signs and symptoms

- The most frequently reported constitutional symptoms are fatigue, insomnia, dizziness, and headaches.1 (Figure 3)

- However, most constitutional symptoms are experienced at a lower severity and frequency when compared with polycythemia vera and MF.1

- The main complications of ET are increased risk and frequency of arterial and venous thrombotic events and transformation to either acute myeloid leukemia or secondary MF.2

Figure 3. Most common constitutional symptoms of essential thrombocythemia*

*Adapted from Khodier and Gadó. 2

Created with BioRender.com

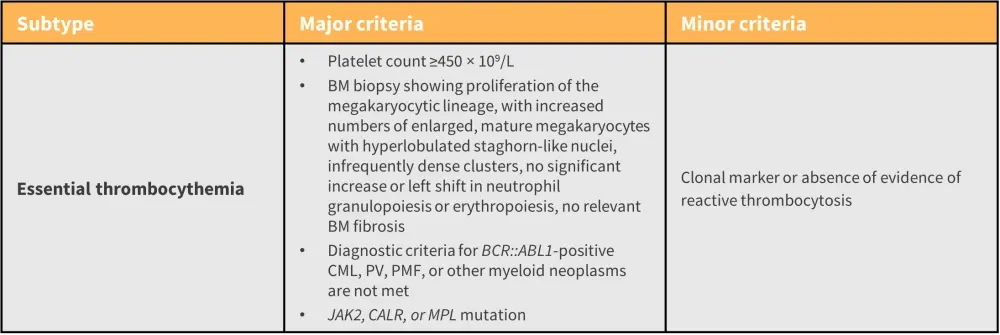

Diagnosis

- A complete blood count, a bone marrow biopsy, and genetic testing are essential for diagnostic confirmation.6

- Historically, the diagnosis of each MPN subtype has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of MPN.

- However, the most recent revision has resulted in a new scheme, the International Consensus Classification of MPN and acute leukemias, with an emphasis on criteria refinement for easier distinction between subtypes (Figure 4).7

- For a confirmed subtype diagnosis, a patient must meet all major criteria defined in the classification, or most of the major criteria together with a minor criterion (Figure 4).7

Figure 4. ICC of MPN and acute leukemias major and minor criteria for the diagnosis of ET*

BCR::ABL1, breakpoint cluster region::Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1; BM, bone marrow; CALR, calreticulin; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; ET, essential thrombocythemia; Hb, hemoglobin; ICC, International Consensus Classification; JAK, Janus kinase; MPL, myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene; PMF, primary myelofibrosis; PV, polycythemia vera.

*Adapted from Arber, et al.7

Prognostic analysis of ET employs two main risk stratification models1

According to The International Prognostic Score for ET:

- Four factors are applied to calculate thrombosis risk: positive history of thrombosis (two points), presence of JAK2V617F (two points), age >60 years (one point), and presence of cardiovascular risk (one point).

- Less than two points define low risk, two points define intermediate risk, and more than two points define high risk.

The more recent Revised International Prognostic Score for ET:

- Three factors are applied to calculate thrombotic risk: age, history of thrombosis, and presence of JAK2 mutation.

- Patients aged <60 years with no other factors are considered low risk, patients with either a history of thrombosis or a JAK2 mutation together with age >60 years are intermediate risk, and patients with all three factors are high risk.

Guidance on diagnosis may vary between countries (see key guidelines section).

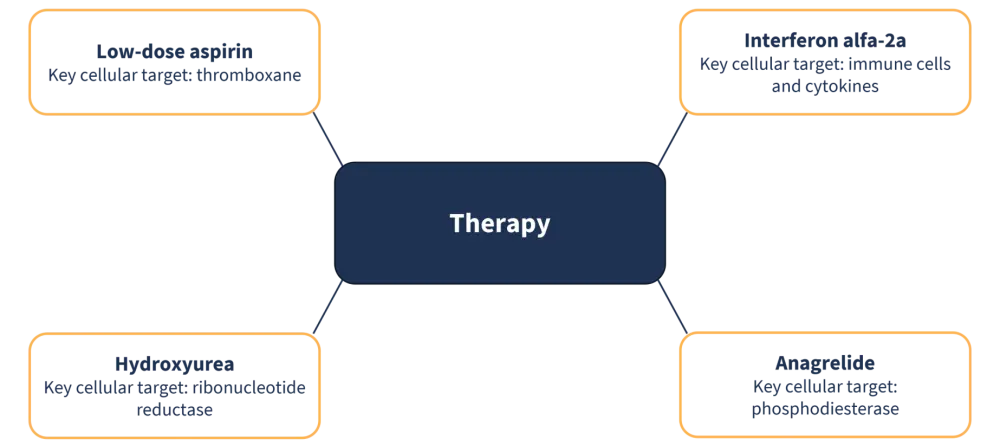

Management2

- For most patients defined as low or very low risk, observation without therapeutic intervention is recommended; however, if any patients also present with cardiovascular risk, then low-dose aspirin is advised.

- The first-line of treatment for intermediate- and high-risk patients is hydroxyurea (HU).

- This can be combined with aspirin if the patient has a positive history of thrombosis.

- For patients who become refractory or intolerant to HU, pegylated interferon alfa-2a is the preferred second-line treatment option.

- Anagrelide is an alternative second-line therapy; however, it is currently only recommended by European LeukemiaNet.

- Major drug classes/types of therapy and their cellular targets used in the treatment of ET are outlined in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Major drug classes and their cellular targets in ET*

*Adapted from Rumi and Cazzola. 8

ET, essential thrombocythemia.

- Treatment with aspirin is associated with a greater risk of bleeding, especially in patients diagnosed with ET.

-

- Other more general side effects include gastrointestinal problems, such as abdominal pain and the development of stomach ulcers after long-term use.9

- HU treatment is associated with the development of anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia.

- Treatment also increases the propensity for leukemic transformation.

- General adverse effects associated with interferon treatment include fever, fatigue, hair and weight loss, and flu-like symptoms.

- Anagrelide is typically well-tolerated by patients; however, common side effects include headache, diarrhea, fatigue, hair loss, and nausea.

Key Guidelines and organizations

- European LeukemiaNet

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

- World Health Organization

- MPN Research Foundation

- MPN Hub visual abstract on key updates to the 5th WHO Classification of MPN

- MPN Hub article on the International Consensus Classification 2022

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content