All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Myelofibrosis: Disease and treatment overview

Do you know... The aggressive nature of myelofibrosis is partly due to its propensity for transformation into acute myeloid leukemia. Approximately, what percentage of myelofibrosis deaths are due to transformation to acute myeloid leukemia?

Myelofibrosis (MF) is the most aggressive myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) disease subtype, characterized by abnormal megakaryocyte proliferation and bone marrow granulocytes.1,2 MF can be divided into pre-fibrotic and fibrotic variants, each presenting at different stages of increased reticulin fibrosis, which ultimately progresses to collagen fibrosis and osteosclerosis.2 The aggressive clinical nature of MF is linked to a propensity for transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which accounts for approximately 20% of deaths.3 Here, we provide a disease overview of MF.

Etiology

- Approximately 65% of patients harbor a mutation in Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), specifically the JAK2V617F mutation3;

- a further 25% harbor a mutation in the calreticulin gene3; and

- around 10% of patients harbor a mutation in the myeloproliferative leukemia gene or are triple negative (negative for JAK, calreticulin, and myeloproliferative leukemia mutations).2

In a healthy individual, JAK2 is responsible for the activation of an intracellular signaling pathway involved in the control of cell proliferation, DNA damage repair, and cellular apoptosis.4 The presence of a mutation leads to loss of the normal inhibitory function of JAK2 and results in the constitutive activation of the JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways.4

Epidemiology

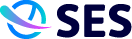

Figure 1. Epidemiology of myelofibrosis*

*Data from Gangat and Tefferi.2; McMullin and Anderson.5; Li, et al.6; Tremblay, Yacoub, and Hoffman.7

Pathophysiology

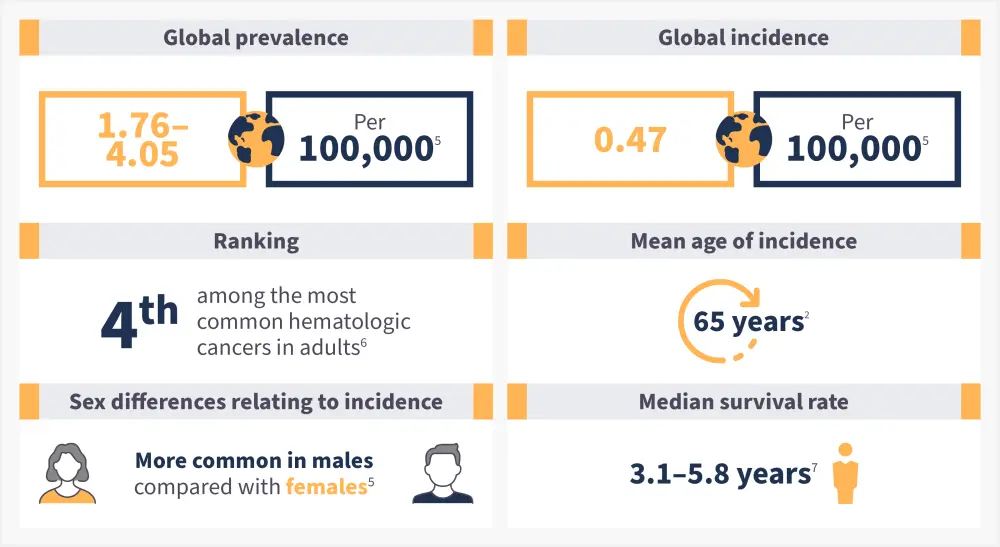

- The main characteristic of MF is clonal proliferation of myeloid cells in the bone marrow.2

- Specifically, monoclonal increases in the myeloid, lymphoid, and erythroid lineages originating from a mutant clone with a stem cell origin (Figure 2).

- It has been proposed that clustering of megakaryocytes and altered expression of the adhesion molecule P-selectin stimulates the release of pro-fibrotic cytokines, such as transforming growth factor beta, platelet-derived growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor.8

- Increased cytokine levels, especially transforming growth factor-beta, increase the deposition of reticulin fibers, collagen types I, III, IV, and V, laminin, and glycoproteins; all of which are known to mediate fibrosis.8

- Transforming growth factor beta also decreases extracellular matrix degradation, which results in a reduction in the proteolysis of collagen and other extracellular matrix components.8

- The result is significant scar tissue buildup within the bone marrow and the development of severe anemia, neutropenia, and leukopenia.8

Figure 2. The molecular pathogenesis of myelofibrosis*

ASK1, Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; CALR, calreticulin; DNMT3A, DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; GATA1, GATA-binding factor 1; IDH1/2, isocitrate dehydrogenases types 1 and 2; IL-18, interleukin 18; JAK, Janus kinase; LOX, lysyl oxidase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; PDGF, platelet derived growth factor; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells; SRSF2, serine and arginine rich splicing factor 2; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases; U2AF1, U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 1;VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

*Adapted from Gangat and Tefferi.2

Signs and symptoms

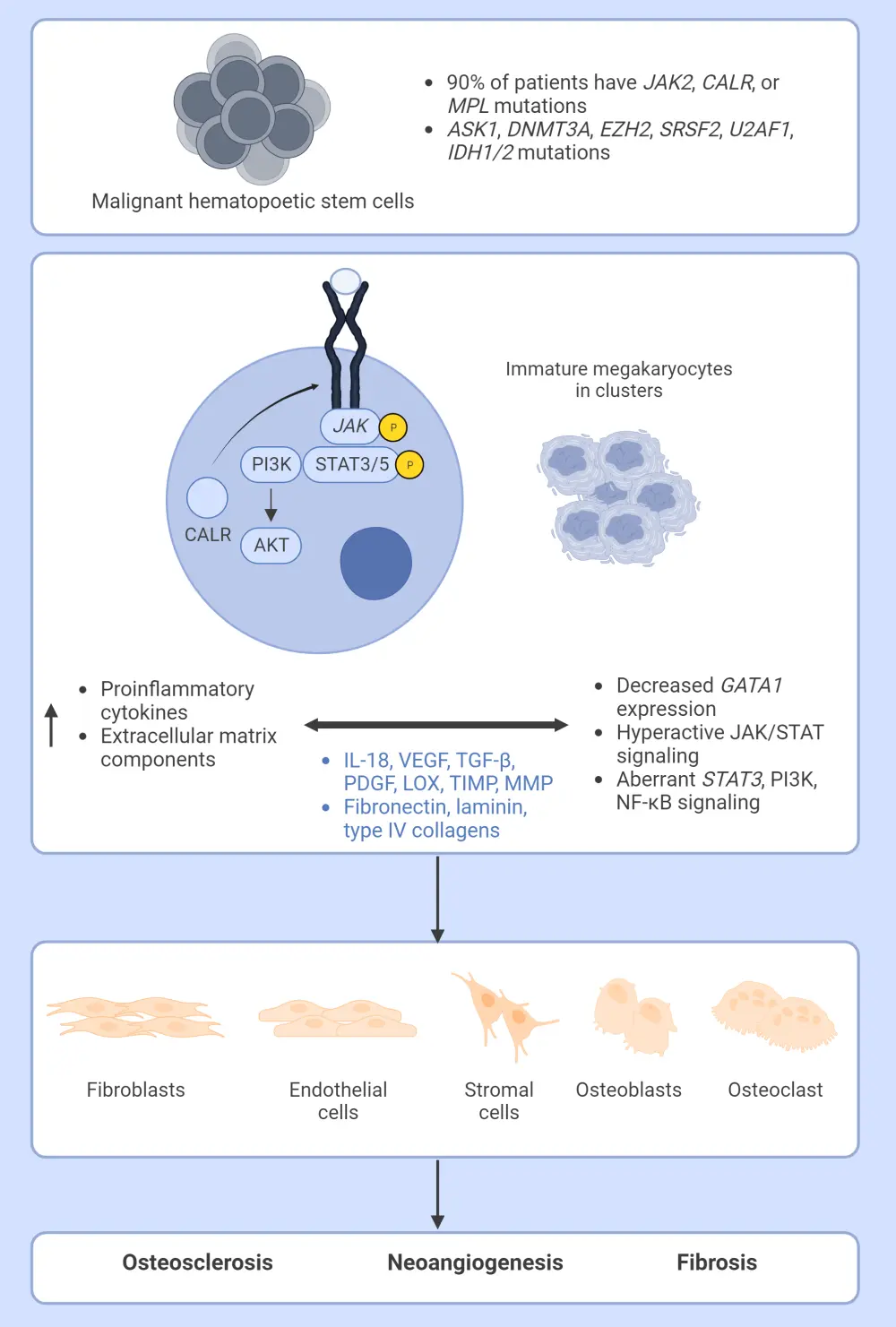

Figure 3. Most common signs and symptoms associated with myelofibrosis*

Created with BioRender.com.

Diagnosis

A review of a bone marrow biopsy is critical to the diagnosis of MF.9 A comprehensive histopathological report, together with a cytogenetic analysis, must also be completed to maximize the diagnostic information given by the biopsy.9

- Identifiable clinical features essential for diagnostic confirmation include,

- patchy hematopoietic cellularity and reticular fibrosis;

- possible megakaryocytes present in clusters and dysplasia;

- distended marrow sinusoids; and

- leukoerythroblastosis with teardrop poikilocytosis.9

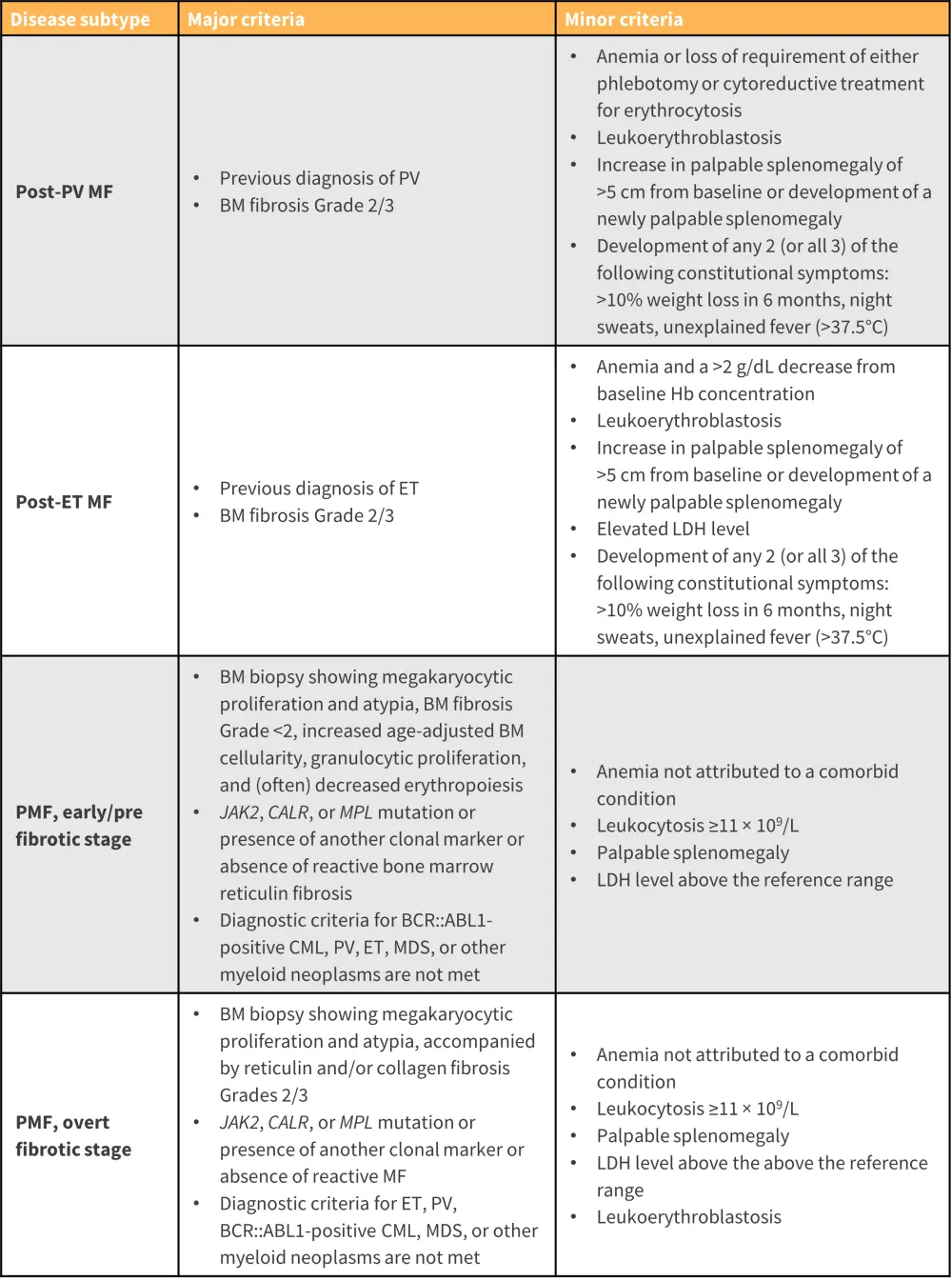

The diagnosis of MF historically has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of MPN; however, the most recent revision has resulted in a new scheme, the International Consensus Classification of MPN, with an emphasis on criteria refinement for easier distinction between subtypes (Figure 4).10

For a confirmed subtype diagnosis, a patient must meet all major criteria defined in the International Consensus Classification, or most of the major criteria together with a minor criterion. Diagnosis should attempt to distinguish MF from other closely related myeloid neoplasms.10

Figure 4. ICC major and minor criteria for the diagnosis of MF*

BCR::ABL1, breakpoint cluster region::Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1; BM, bone marrow; CALR, calreticulin; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; ET, essential thrombocythemia; Hb, hemoglobin; ICC, International Consensus Classification; JAK, Janus kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MF, myelofibrosis; MPL, myeloproliferative leukemia virus; PV, polycythemia vera; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

*Adapted from Arber, et al.10

Prognostic analysis for MF employs several risk stratification models3

The International Prognostic Scoring System:

- Applies five independent predictors of inferior survival,

-

- age >65 years, hemoglobin <10 g/dl, leukocyte count >25 × 109/L, circulating blasts ≥1%, and presence of constitutional symptoms; and

- presence of 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 adverse factors define low, intermediate-1, intermediate-2 and high-risk disease categories, respectively.

The Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System:

- Uses the same variables as the International Prognostic Scoring System; however, two points instead of one are assigned to hemoglobin <10 g/dl.

- Risk categorization was modified to low (0 adverse points), intermediate-1 (1/2 points), intermediate-2 (3/4 points), and high (5/6 points).

The Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System plus:

- Incorporates three additional risk factors:

-

- Platelet count <100 × 109/L, red cell transfusion needs, and unfavorable karyotype

- Risk categorization is set as low (no risk factors), intermediate-1 (1 risk factor), intermediate-2 (2/3 risk factors), and high (≥4 risk factors)

Three further prognostic models were recently developed:

- Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System for transplant-age patients

- Karyotype-enhanced MIPSS70

- The genetically inspired prognostic scoring system

Newer models incorporate factors associated with driver mutations among others, karyotype, and sex-adjusted hemoglobin levels.

Management

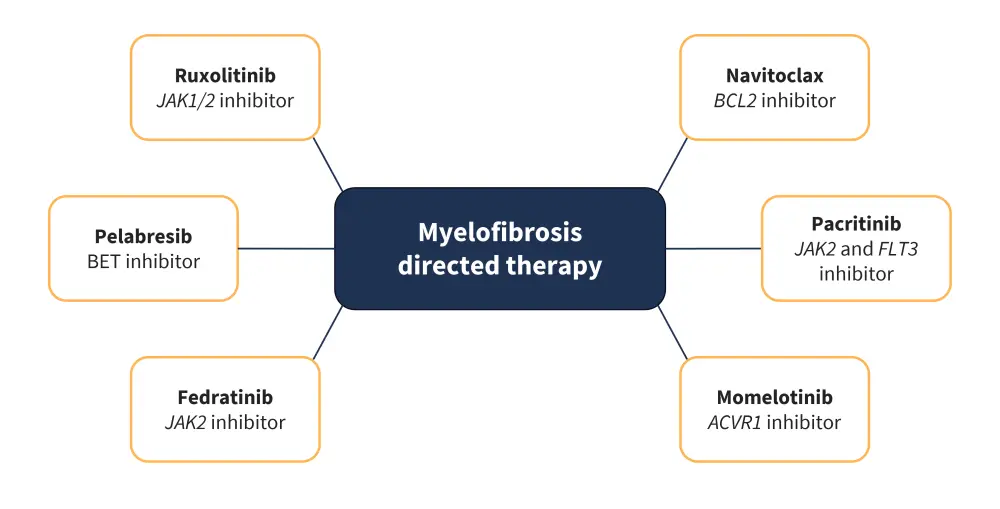

Despite the aggressive clinical nature of MF, research surrounding the JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway has yielded positive results in the form of JAK inhibitor (JAKi) therapy (Figure 5).

- The first U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved JAKi treatment was ruxolitinib, which inhibits JAK1/2 and is considered the standard of care for patients with symptomatic, intermediate, or high-risk disease; further analysis has shown clinical benefit in patients with symptomatic low-risk disease.8

- Fedratinib was the second approved JAKi, with clinically selective activity against JAK2, and was approved for use in patients with intermediate-2 and high-risk disease and in the second-line treatment setting for patients who have become refractory or intolerant to ruxolitinib.8

- The third JAKi approved was pacritinib, a multikinase inhibitor with clinical activity against JAK2, FLT3 (fms-like tyrosine kinase 3), IRAK1 (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1), and CSF1R (colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor); treatment is specifically used in thrombocytopenic patients with a platelet count <50 × 109/L.11

- Momelotinib is another JAKi with clinical activity against JAK1, JAK2, and activin A receptor type 1, used as a second-line therapeutic option for patients refractory or intolerant to ruxolitinib and treatment induced anemia; it was recently approved by the U.S. FDA in September 2023.12

- Newer approaches include the addition of navitoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor, to ruxolitinib for patients who have developed resistance to other JAKi and are diagnosed with persistent or progressive MF.11

- Pelabresib, a bromodomain and extraterminal domain inhibitor, both as a single agent and in combination with ruxolitinib is another option considered for both first-line and refractory settings in MF.11

- Currently, the only form of therapy that has shown measurable disease modification and curative ability is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.11

Figure 5. Myelofibrosis directed therapies and their molecular targets*

ACVR1, activin receptor type 1; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BET, bromodomain and extra-terminal; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; JAK, Janus kinase.

*Adapted from Venugopal and Mascarenhas. 11

- Key complications associated with JAKi treatment include,

-

- anemia;

- neutropenia;

- leukopenia; and

- increased risk of infection.3

B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitors, such as navitoclax, are associated with dose-dependent thrombocytopenia and neutropenia.12 The hematologic adverse events of pelabresib include thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia.2 Other common non-hematologic adverse events include diarrhea, nausea, and fatigue.2

Key Guidelines and organizations

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content