All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MPN Advocates Network.

The mpn Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mpn Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mpn and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The MPN Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AOP Health, GSK, Sumitomo Pharma, and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MPN content recommended for you

Primary myelofibrosis: Prognostic impact of non-driver mutations

Patients diagnosed with primary myelofibrosis (PMF) often present with non-driver mutations which are related to other myeloproliferative neoplasms. The presence of these non-driver mutations can influence the clinical phenotype and treatment response.

Recently, Hernández-Sánchez et al.1 published results from a study in American Journal of Hematology investigating the impact of non-myeloproliferative neoplasm driver mutations in patients diagnosed with PMF. We summarize the key points below

Study design1

- This study was performed across 60 Spanish sites (N = 312)

- Median age was 68 years

- A total of 20 genes out of 56 evaluated were consistently analyzed across all next-generation sequencing panels.

- Only pathogenic or likely-pathogenic variants with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of >1% were considered a mutation.

Key findings1

- Non-driver mutations were identified in 72% of patients and 47% of patients had ≥2 non-driver mutations

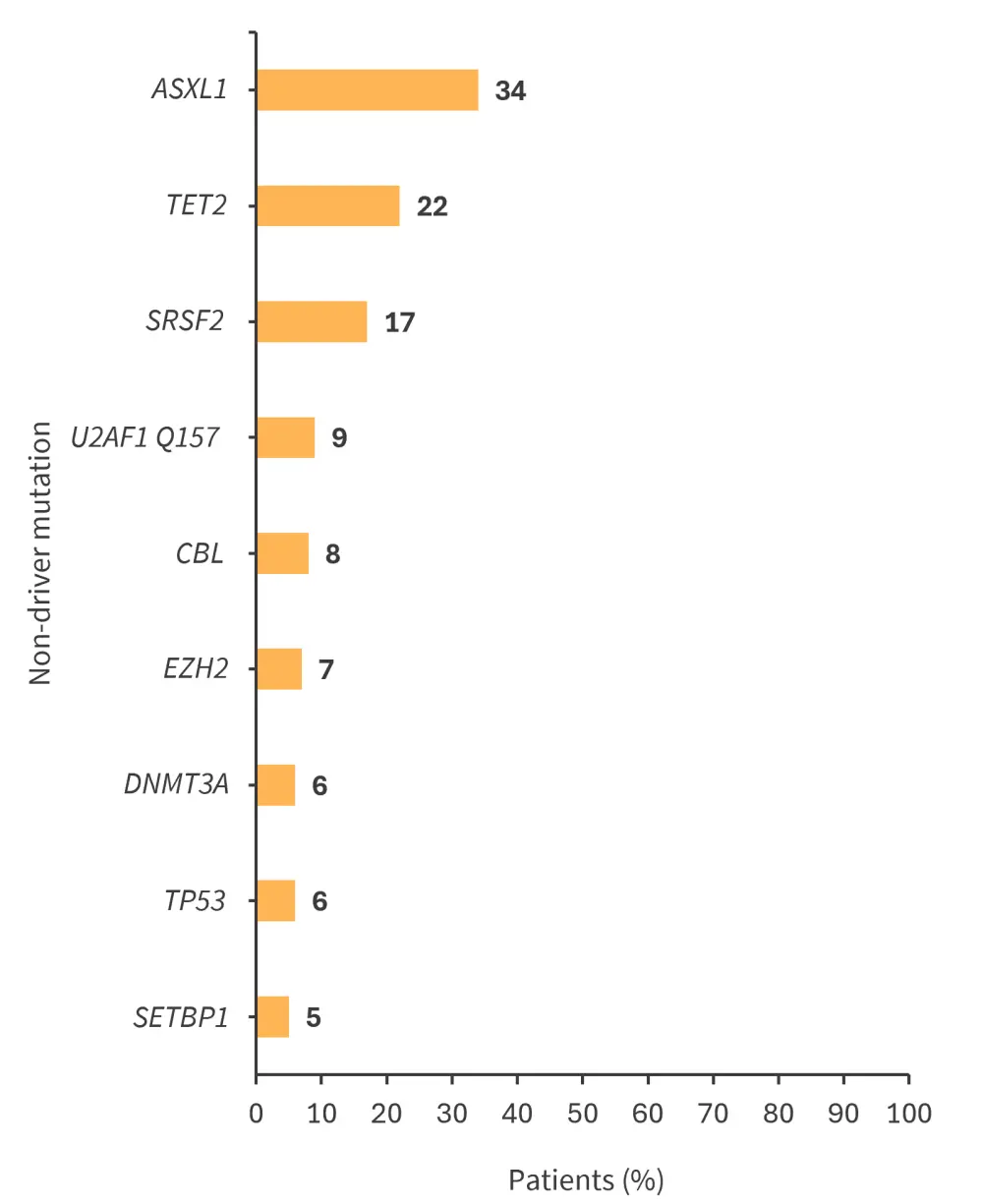

- The most frequently identified non-driver mutation was ASXL1, followed by TET2 and SRSF2 (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Most frequently identified non-driver mutations in patients with PMF*

*Adapted from Hernández-Sánchez, et al.1

- The presence of any non-driver mutation resulted in a worse median overall survival (OS) vs patients with no non-driver mutations (p < 0.001)

- 0 mutation: 12.4 years

- 1 mutation: 8.7 years

- ≥2 mutations: 4.4 years

- A VAF of >20% was shown to be an adverse prognostic factor

- Univariate analysis identified the following mutations to be associated with shorter OS: SRSF2 (p < 0.001), CBL (p < 0.001), SETBP1 (p = 0.012), TP53 (p = 0.016), U2AF1 Q157 (p = 0.021), NRAS (p = 0.032), and EZH2 (p = 0.034).

- Mutations identified as independent prognostic factors were: SRSF2 (p < 0.001), CBL (p = 0.003), EZH2 (p = 0.013), SETBP1 (p = 0.024), and ASXL1 with a VAF of >20% (p = 0.042).

|

Key learnings |

|---|

|

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content